Barriers to biosimilar market growth

Biosimilar new entry was expected to shake up the pharmaceuticals market, leading to lower prices and increased access to drugs. However, market access has been slower than many predicted, with some citing concerns around anti-competitive practices limiting entry and expansion. This is reflected in the European Commission DG Competition’s 2021 Management Plan, which anticipates that the Commission will continue investigating anti-competitive practices that lead to delays in the entry of biosimilars and generics.[i] In this article, we explore the economic benefits from biosimilar competition and consider both demand and supply-side factors that might be limiting growth.

What is a biosimilar?

Biological medicines (“biologics” or “originators”) are a class of drugs made primarily from biological sources. They are one of the costliest drugs in the market as they are expensive and complicated to develop. Patents offer a time-limited opportunity for manufacturers to earn a financially sustainable return on investment.

Biosimilar medicines are similar to a biologic, although, due to the natural variability involved in their development, they are not an exact replica of the biologic and cannot be considered a “generic”. This natural variation requires a more lengthy and costly development and regulatory approval process than for generics. However, it also allows for some product differentiation and non-price competition in the market.

The benefits from the growth of biosimilars

As of June 2020, there were 58 biosimilars approved for 16 reference products in the EU (including the UK). Biosimilars are typically priced at an initial list price discount of circa 10% to 30% to the originator, although there are reports of differences as high as 70% once discounts are considered.[ii] Prices continue to fall as additional biosimilars enter and originators respond by price cutting.

The total retail spend on pharmaceuticals in the EU (excluding hospital care) is estimated at being more than €210 billion,[iii] of which €93 billion is estimated to be on biosimilars (up from €55bn in 2018).[iv] In 2017, the EU spent 9.6% of its GDP on healthcare – pharmaceuticals account for approximately 20% of that expenditure.[v]

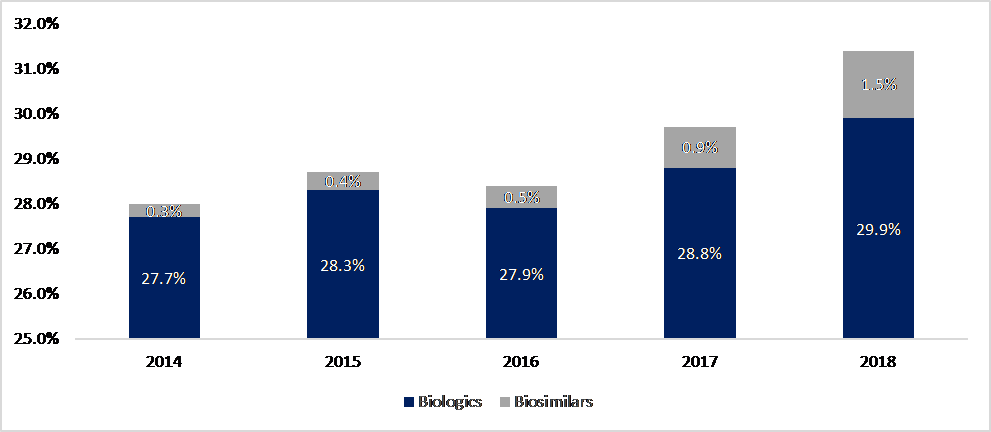

Figure 1: Proportion of European healthcare spending on biologic molecules 2014-2018

Source: Troein, Newton, Patel and Scott (2019).

Whilst the share of biosimilars in the biologics market is increasing, it represented only 5% of treatment days in 2018, rising to 9% in 2020. When considering spend, the share of biosimilars has fallen: this is because the growth of biologicals has been so huge that savings in markets with biosimilar competition have been more than offset by spend on originators in markets without competition.

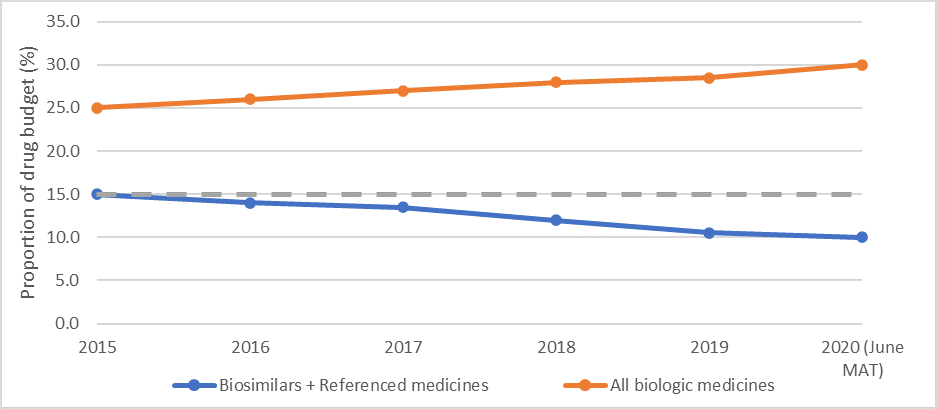

Figure 2: Proportion of drug budget spent on biologics and biosimilars 2015-2020

Source: IQVIA data (21 January 2020)

Given the large markets for these drugs (for example, global annual sales of adalimumbab and beczamizumab amounted to circa US$19 billion and US$7 billion, respectively) and the high margins available to biosimilar producers, the growth in biosimilars is slower than expected. Consequently, the benefits of price competition are not being realised by national health systems and insurers who are the typical purchasers. It has been estimated that biosimilars entry could generate savings of circa €100 billion over five years across Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the UK and the US, [vi] with NHS England estimating savings of circa £400 million to £500 million.[vii] These savings could be used to increase access, with increased usage most likely to occur in those markets with a low starting usage.

Demand for biosimilars

The take-up of biosimilars is driven by both demand and supply-side factors. That is, it requires companies to supply biosimilars and a willingness for existing patients to switch to these drugs and/or those being treated for the first time to use them. On the demand side, there are three decision-makers who facilitate the take-up of a biosimilar:

- The payer. National/ regional authorities and insurers decide which drugs are available to prescribe, procure and negotiate the price of the drug (often through tenders), reimburse the cost of drugs to doctors/ pharmacists and set the guidelines and incentives for prescription and dispensing.

- The prescriber. Clinicians prescribe, and pharmacists dispense drugs from among the options available, depending on their assessment of clinical need, clinical guidelines and any incentives. This is increasingly done in consultation with patients.

- The user. Patients who use the drug, in consultation with clinicians.

The payer is more likely to be influenced by price factors, while non-price factors, including regulatory constraints, product differentiation and behavioural inertia, drive demand by prescribers and users.

Price differential

Switching from a biologic to a biosimilar is not a costless exercise. There are costs involved in negotiating the price of the drug or running a tender exercise; and in passing the knowledge to clinicians and patients on how the drugs are to be administered.[viii] Other switching costs can include training healthcare professionals on new products or stocking and dispensing additional products. For a biosimilar to be successful, the price differential between the biological and the biosimilar needs to be sufficient to compensate for these switching costs.

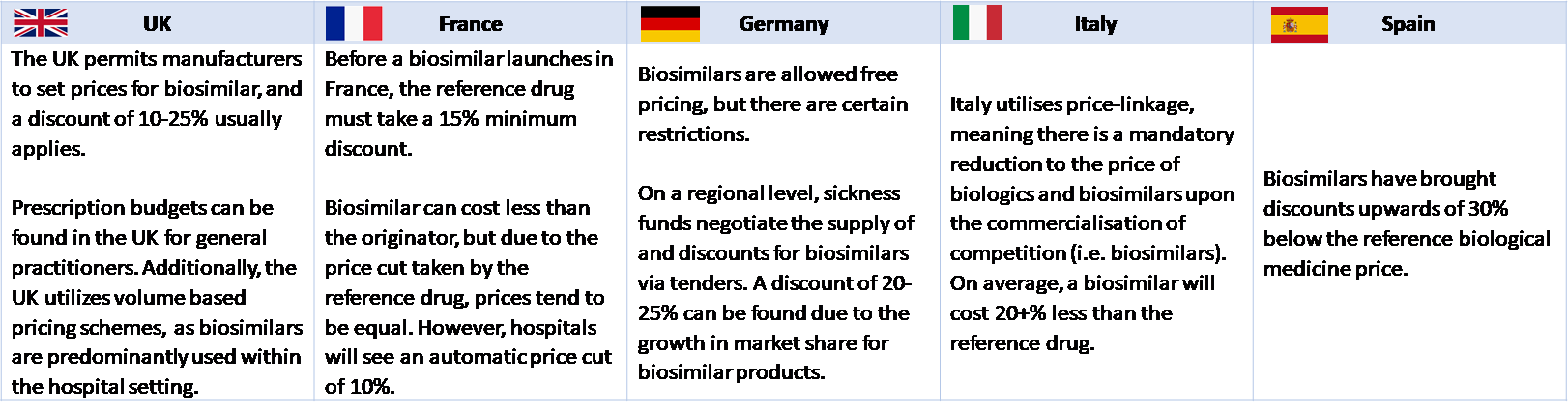

The relative price difference between an originator biologic and its biosimilars tends to be significant.[ix] While it depends on a specific country’s pricing mechanism, it is generally greater than c. 10-30% in EU Member states and the UK. Data from 25 European countries shows that 18 of the 25 countries have mandatory discounting in place where the price of the biosimilar should be lower than the price of the biologic.[x] For example, in Finland, the wholesale price of the first reimbursable biosimilar must be at least 30% lower than the approved wholesale price of the reference product; in Ireland, the price of the biosimilar is 10-20% below the price of the reference product; and in Italy, biosimilars are priced approximately 20% below the price of the reference product.[xi] The figure below shows the pricing policies for five major European countries.

Figure 3: Pricing of biosimilars across selected European countries

Source: Precentric One, Biosimilar Pricing in Europe: A look at Infliximab

Despite the potential price differential, the growth of biosimilars in the relevant market may be slow. First, it may take time for an Authority to decide to procure a biosimilar and for an agreement to be reached: tenders may only be run at predefined intervals and/or pricing negotiations can take many months or years as Authorities seek to ensure that they receive value for money. However, there is evidence that Authorities are becoming increasingly sophisticated at boosting competition between suppliers of biosimilars and the originator and between biosimilars.

Second, even once an agreement is in place between an Authority and the biosimilar manufacturer, the impact of the biosimilar is being dampened due to the role of the prescriber and the user as co-decision makers. Given that the users’ spend on the drug is usually fully reimbursed, their preferences are predominantly non-price driven so that the cost differential becomes less decisive a factor.

Regulatory constraints and incentives to prescribe

Clinical guidelines around prescribing and interchangeability/ switching vary by country and may reduce the prescribing discretion of clinicians.[xii] Further, any automatic substitution by pharmacists is generally not allowed for biologic medicines due to their natural variability.[xiii] However, once licenced, Authorities frequently use financial incentives and the setting of prescribing budgets and quotas to promote the use of lower-cost biosimilars. Out of 24 European countries for which data is available, 14 have such financial incentives for prescribing in place.

Product differentiation

A biosimilar is not an identical copy of the originator, so there may be concerns over its efficacy or safety. A 2018 review of 90 studies showed no reported differences in immunogenicity, safety, or efficacy of biosimilars.[xiv] However, clinical discretion remains a key driver of prescription decisions, and it takes time for clinicians to trust the clinical efficacy and safety of a new drug, especially due to concerns around immunogenicity.[xv][xvi],[xvii] Building credibility and trust among clinicians requires biosimilar manufacturers to engage with clinicians to provide information and education around the safety of the drugs,[xviii] which takes time. This may create a lag between biosimilar new entry and it being prescribed routinely.

Behavioural inertia

The pricing of the drug is likely to play only a limited role in informing patient preferences in Europe, as patients typically do not pay (at least, in full) for the drug. Therefore, a patient who is already using a biologic may not perceive any direct benefit from switching and might be reluctant to do so. Patients may also be reluctant to switch due to concerns around the clinical effectiveness of a new or different drug, particularly in the context of the nocebo effect (where the negative expectations of the patient negatively impact the treatment outcome)[xix][xx],[xxi] or where the drug has a different method of delivery, for example, a syringe or an autoinjector pen.

This may mean that an originator biologic product builds a cohort of potentially locked-in patients during the period of market exclusivity, and the growth of biosimilars is limited by the number of new patients.

Barriers to entry and expansion

Supply-side considerations and constraints may impede the success of biosimilars in entering the market or gaining a sustainable market share, thus acting as a disincentive for potential manufacturers to develop and commercialise biosimilars. Potential barriers relate to the economics of biosimilars supply, market conditions, and regulatory protections.

The high cost of development and commercialisation

Potential entrants are faced with significant upfront costs for developing a biosimilar and bringing it to the market – both time and monetary costs. Capitalising on the opportunity in the biological molecule market requires significant investment in research and development and then navigating the regulatory, manufacturing, and sales and marketing route to market. It is estimated that it could take at least four years and between U$100 million to US$300 million to bring a new biosimilar to the market.[xxii],[xxiii]

Common with other product markets, potential biosimilar manufacturers are faced with uncertainties about the market and the competitive response by existing suppliers (manufacturers of the biologic and other biosimilars). This uncertainty is exacerbated by the potential for slow uptake (which is likely slower in smaller markets) and regulatory restrictions; and, often, the fact that there is limited scope for the market to expand, so that market share gains are only achieved via substitution. However, the main difference to other markets is the need to recover the large costs of R&D. A report by IQVIA suggests that only a third of biosimilars can be expected to achieve sales above US$100 million – thus potentially covering the anticipated cost to bring a new biosimilar to the market.[xxiv]

Uncertainty about demand

As set out above, on the flip side of the significant costs to enter, another potential disincentive relates to the observed low and/or slow uptake of new biosimilars. Potential suppliers need to be able to secure sufficient sales to make their investment worthwhile – profitability is uncertain in an environment where:

- Demand is suppressed by factors such as stickiness on the part of health authorities, clinicians or patients;

- There may be groups and parts of the market that are non-contestable due to patients being locked-in to the use of the originator;

- The time lag between the development of biologic and the entry of biosimilars (time for a patent to expire, entry to occur, and biosimilar to establish its presence in the market) may result in a shift in treatment methods and technologies, which have to alter the requirements and competitive dynamics at the time of successful commercialisation; and

- There exist regulatory restrictions (or potential for delays or abuses of the regulatory and IP processes) and prospect for litigation.

Response by existing market participants

At the time when a potential supplier is considering the development of a biosimilar or later when the launch is being contemplated, there is already one (biologic manufacturer) or more (other biosimilars manufacturers) participants in the relevant market. There is scope for them to deploy strategies that discourage entry or make it unprofitable. Anticipating such behaviour will deter entry or expansion by biosimilars suppliers. Such strategies may include the following.

- The biologic manufacturer may lower its price so as to retain its market share, especially for patients who may be reluctant to switch and clinicians who may take time to trust the clinical efficacy of biosimilars. Whilst this may result in a biosimilar not entering the market, the savings associated with such entry are achieved. It is when this is done with a view to increasing price again when the threat of entry is no longer present that this response may be harmful, given the costs associated with R&D.

- Similarly, a competitive response that discourages entry (or makes it more difficult) is innovation on the part of the biologic. To the extent this brings clinical and/or cost benefits, potential instead of actual competition achieves a positive outcome for patients and the health system.

- There may be additional protections in place for the biologic after the originator patent expires. This may be through additional patents covering dosing, formulations, delivery and medical use. As with other products relying on IP rights, in some cases, biologics manufacturers may be able to exploit the patent process to artificially raise barriers to a new entry.

- Finally, there is potential for the originator supplier to engage in exclusionary behaviour to raise the cost of rivals’ entering the market and their ability to compete effectively. This comes in the form of predatory pricing (an extreme case of the price response outlined above), exclusivity clauses or conditional rebates in contracts with customers etc.

While the above strategies are varied, from competitive responses to potential abusive conduct, they have the effect of discouraging entry – if anticipated or if such a reputation of aggressive response has been built by the existing supplier(s) – or resulting in the exit of rivals. (However, note that in the latter case, the high sunk costs may act as a commitment mechanism that prevents exit.)

Looking to the future

Demand and supply constraints impact the ability of biosimilars to enter the market or expand their market shares. There are actions that regulators, competition authorities and health authorities could consider to both reduce barriers and ensure that the benefits of increased competition flow through to purchasers and patients, if these fail to be realised. Although due to the complexity of the market and the interplay between characteristics, this might require a multi-faceted approach.

Competition authorities

Competition authorities have been particularly concerned about strategies and tactics by biologic manufacturers that may keep prices high and hamper access to cheaper medicines. This includes, for example, investigating “pay-for-delay” strategies,[xxv] mergers that may adversely effect the incentive of the merging parties to innovate,[xxvi] or foreclosure concerns in cases where there is a need for access to an essential input.[xxvii]

There is often a tension between investigations by competition authorities and the award of patents. Where low entry is due to the dominant position held by the biologic manufacturer, this may be complicated by the presence of patents that are naturally intended to create a “monopoly” for a period of time in order to incentivise investment. What is important then is for the authorities to establish whether this monopoly position has been abused to entrench their market power going forward, and the mechanism for doing so.

Patent offices

Patent offices face a dichotomy. On one hand, patents must be granted with sufficient ease to encourage R&D but on the other hand but not so casually they prevent innovation by others. Particularly with regards to the use of divisional and other measures that extend patents, there may be a mid-way house that requires these to be filed sufficiently in advance of expiry of the initial patent to give time for challenge without unnecessarily delaying valid new entry.

Health authorities

Health authorities may also want to consider their licensing, pricing and charging mechanisms – to enable faster uptake of biosimilars. For example, NHS England has actively sought to tender the best priced biological medicines in the market. As a result of this strategy, the uptake of the etanercept biosimilar at more than 80%.[xxviii]

How A&M can help?

A&M Economics provides expert economic advice to clients and their legal advisors on all aspects of competition law, including potential abuse of dominance and patent abuses in the healthcare and life sciences market. We use economic techniques to estimate potential harm from these practices and to develop innovative remedies. For more information, please contact Schellion Horn, Raymond Berglund, Matt Tavantzis or Diana Wong.

To read more on this topic, check out our article "Biosimilars: where will the market be in five years?"

[i] European Commission, Management Plan 2021 – DG Competition, March 2021 [https://ec.europa.eu/info/system/files/management-plan-comp-2021_en.pdf]

[ii] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/pharmaceuticals-and-medical-products/our-insights/five-things-to-know-about-biosimilars-right-now#

[iii] Based on 2016 figure published by the EU and WTO, uplifted by the annual growth rate of the past 5 years.

[iv] Troein P, Newton M, Patel J, Scott K (2019) The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe. IQVIA

[v] Ibid, p. 46

[vi] https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/european-report-finds-generics-and-biosimilars-key-to-curbing-wasteful-drug-spending

[vii] https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/what-is-a-biosimilar-medicine-guide-v2.pdf

[viii] See, for example, “Short-term costs associated with non-medical switching in autoimmune conditions”, and “The Resource Cost of Switching Stable Rheumatology Patients From An Originator Biologic To A Biosimilar In The UK”

[ix] Moorkens E, Vulto AG, Huys I, Dylst P, Godman B, Keuerleber S, et al. (2017) Policies for biosimilar uptake in Europe: An overview. PLoS ONE

[x] Precentric One, Biosimilar Pricing in Europe: A look at Infliximab: https://www.eversana.com/insights/biosimilar-pricing-in-europe/

[xi] Moorkens E, Vulto AG, Huys I, Dylst P, Godman B, Keuerleber S, et al. (2017) Policies for biosimilar uptake in Europe: An overview. PLoS ONE

[xii] Moorkens E, Vulto AG, Huys I, Dylst P, Godman B, Keuerleber S, et al. (2017) Policies for biosimilar uptake in Europe: An overview. PLoS ONE

[xiii] Moorkens et al (2017) data shows that prescribing substitution is only allowed in 5 out of 24 countries covered by the study.

[xiv] Cohen HP, Blauvelt A, Rifkin RM, Danese S, Gokhale SB, Woollett G (2018). Switching Reference Medicines to Biosimilars: A Systematic Literature Review of Clinical Outcomes. Drugs.

[xv] Hemmington A, Dalbeth N, Jarrett P, Fraser AG, Broom R, Browett P, Petrie KJ. (2017) Medical specialists' attitudes to prescribing biosimilars. Pharmacoepidemiol and Drug Safety

[xvi] Waller J, Sullivan E, Black CM, Kachroo S (2017) Assessing physician and patient acceptance of infliximab biosimilars in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis across Germany. Patient Preference and Adherence

[xvii] Beck M, Michel B, Rybarczyk-Vigouret MC, Levêque D, Sordet C, Sibilia J, Velten M; CRI (2016). Rheumatologists' Perceptions of Biosimilar Medicines Prescription: Findings from a French Web-Based Survey. BioDrugs

[xviii] Edwards C.J., Hercogová J, Albrand H and Amiot A (2019) Switching to biosimilars: current perspectives in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy

[xix] Avouac J et al. (2018) Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: The experience of Cochin University Hospital, Paris, France. Seminars in Arthritis Rheumatism

[xx] Boone NW et al. (2018) The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology

[xxi] Jacobs I, Singh E, Sewell KL, Al-Sabbagh A, Shane LG (2016) Patient attitudes and understanding about biosimilars: an international cross-sectional survey. Patient Preference and Adherence

[xxii] Troein P, Newton M, Patel J, Scott K (2019) The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe. IQVIA

[xxiii] Blackstone E. A., Joseph, P. F. (2013). The economics of biosimilars. American health & drug benefits

[xxiv] Troein P, Newton M, Patel J, Scott K (2019) The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe. IQVIA

[xxv] Originators seeking to protect their market shares by paying the generic/ biosimilar manufacturers to stop or delay entry into the market.

[xxvi] For example, in the Pfizer/Hospira case (Case No Comp/M.7559), the European Commission was concerned that the merger would restrict the development of the competing biosimilar.

[xxvii] Where the biologic manufacturer is also the producer of a key (often, patented) input into the development of the biosimilar, the biologic manufacturer may restrict its competitors’ access to such inputs.

[xxviii] https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/overcoming-challenges-biosimilars-market