Renewable Energy Tax Incentives: Production and Investment Tax Credits Structure & Diligence Considerations

With the economy looking to recover from the pandemic, investors searching for tax incentives, and the Biden administration’s focus on clean fuel, renewable energy projects present an opportunity for investors. An investor’s return from a US renewable energy project requires an appreciation for the nuances of the project’s legal, capital, and tax structure. In this article, we discuss the key tax considerations an infrastructure investor should consider as the supporting financial model is prepared and due diligence is performed.

Currently, there are two US federal tax credit mechanisms aimed at promoting renewable energy projects:

1. Production tax credit (PTC)[1] was enacted in 1992 as part of the Energy Policy Act and has been extended over a dozen times, most recently in connection with the Consolidated Appropriations Act, the second relief bill aimed at providing economic relief from COVID-19 disruptions.[2]

2. Investment tax credit (ITC)[3] was enacted in 2005 and has been repeatedly extended.[4]

The Credits (collectively, PTC and ITC) were enacted to encourage investment in assets that otherwise would not be economically feasible when compared to traditional energy production (i.e., oil and gas). Given the repeated extensions of the Credits, and President Biden’s executive orders related to the oil and gas and renewable energy industries, it appears renewable tax credits (or some form thereof) are here to stay.

Production Tax Credit (PTC)

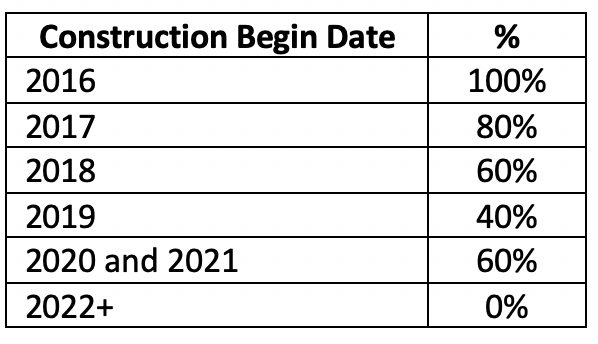

PTCs were established as an incentive for the construction of wind turbines for electricity generation and the credit currently stands at 2.5 cents per kilowatt-hour (kwh) of electricity produced and sold to an unrelated person for a 10-year period beginning on the date placed into service.[5] PTCs are phased out depending on the date that construction on the project began. The credit for wind facilities is phased out as follows:[6]

Further, construction must be “continuous” from the beginning of construction until the asset is placed into service for that vintage year’s PTC per kwh to apply for a project.[7] To determine when construction begins, the IRS applies a physical work test, which is focused on when physical work of a significant nature began. The focus is on both the nature and quantity of the work. The IRS has also provided a “5% safe harbor” for the begun construction test, which asks whether 5% of a project’s depreciable basis in eligible property is spent prior to the end of the initial year.[8] A project must also be placed into service within four years after the end of the year in which construction began (five years if construction began in 2016 or 2017, due to COVID relief measures) to establish the phase-out year.[9] For example, if construction began in 2016 (by satisfying the 5% safe harbor), was maintained continuously for five years, and was placed in service in 2021, then one may generally feel comfortable claiming a 2.5 cents per kwh PTC.

Investment Tax Credit (ITC)

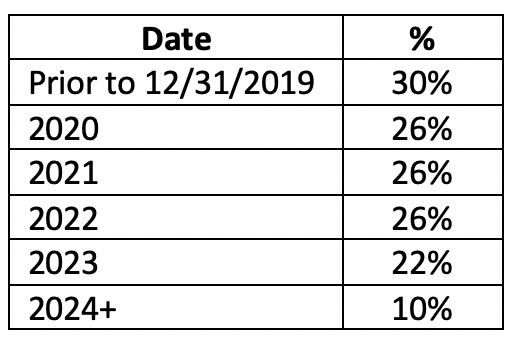

ITCs allow taxpayers to claim a one-time tax credit as a percentage of the cost of qualified energy property placed in service.[10] Qualified energy property includes solar PV panels, inverters, racking, balance-of-system equipment, installation costs, and step-up transformers, but generally does not include operating reserves, permanent loan fees, or transmission lines.[11] Similar to PTCs, ITCs (allowed for solar projects) are based upon the date construction begins and are phased out annually, as follows:[12]

Unlike PTCs, to the extent an ITC is claimed, the depreciable tax basis of such related property must be reduced by 50% of the ITC amount.[13] Additionally, unlike PTCs, which are based on prospective production over a 10-year period, the one-time ITC is subject to recapture over the subsequent five-year period.[14] Recapture is triggered if the qualified energy property is sold within five years of the date placed into service.[15] This recapture would also be triggered if the taxpayer, who benefits from ITC, were to sell its equity interest in the project company or if the project ceases to be eligible for ITCs during the recapture period.[16] The recapture amount is reduced by 20% for each full year that elapses following the date placed into service.[17]

Tax Equity Provides the Financing

Many investors and developers of renewable projects do not otherwise have sufficient US federal income tax liability to fully benefit from the tax shield provided by accelerated depreciation and the Credits. However, they are often able to monetize these incentives for a renewable energy project by structuring the transaction with an investor that can readily use the resultant tax benefits. These investors are known as tax equity investors. Through specific renewable investment structures, tax equity investors can provide financing to the projects in exchange for the lion’s share of the tax incentives. These structures typically provide a mechanism through ownership or a lease whereby the tax equity investor maintains an interest in the project for a period of time sufficient to capture the vast majority of the tax incentive benefits, following which the majority of the project economics (e.g., income, Credits, etc.) revert to the sponsor.

Renewable Investment Structures

The most common structure for renewable energy projects is the partnership flip. In this structure, an investor, usually a taxable entity, like a C corporation (“Tax Equity Partner”), generally provides 35% to 50% of the project capital in exchange for negotiated benefits (e.g., ITCs/PTCs and depreciation). The partnership flip can be structured as a fixed date flip or, more commonly, as an internal rate of return (IRR) flip, wherein the Tax Equity Partner’s IRR is earned through the allocation of 99% of tax credits, taxable income/losses and distributable cash. After the flip date, the Tax Equity Partner is typically allocated only 5% of taxable income/losses and the sponsor is allocated the remainder. However, in general practice, the Tax Equity Partner often exits the project at the flip date or shortly thereafter. The duration until a partnership flip date can vary, depending on whether the flip is time-based or return-based (time-based flips range from 5.5 to 6 years; return-based flips range from 5.5 to 7 years).

A smaller percentage of tax equity transactions are inverted lease structures wherein the Tax Equity Partner typically provides 20% to 40% of the project capital. In these transactions, the developer leases the assets to the operator (a partnership owned by the developer and Tax Equity Partner) who elects to pass through the ITC to the Tax Equity Partner (e.g., 99% of credits), but generally retains all, or a majority, of the tax depreciation to offset future lease revenue. The operator enters into a power purchase agreement to sell the energy and makes lease payments to the developer to cover debt service. The operator is also required to recognize half of the ITC as income on a pro-rata basis over five years. The duration of an inverted lease structure can range from 7 to 24 years and may include up to 20% as prepaid rent. The prepaid rent is usually treated as a loan for tax purposes and recognized over the duration.

The sale-leaseback is the least common structure for investing in renewable energy projects. A Tax Equity Partner theoretically provides capital equal to a project’s full fair market value, but the developer usually returns 15% to 20% of that value at inception designated as prepaid rent. The Tax Equity Partner (lessor) purchases the relevant assets from the sponsor (lessee) and the sponsor leases back the project. This allows the Tax Equity Partner up to three months after the project is placed in service to close on the tax equity financing. The duration varies based upon lease terms, and the designated prepaid rent is usually treated as a loan for tax purposes and recognized over the duration. Ultimately, the Tax Equity Partner receives the ITC, based upon the purchase price, and accelerated depreciation.

Tax Diligence & Structuring

A renewable energy investor’s PTC tax due diligence should focus on the date construction began and whether construction was continuous. In addition, if relying on the safe harbor, it is necessary to understand the tax basis of property placed in service in the initial year. For ITCs, tax due diligence should include a focus on the evaluation of the developer’s analysis of costs eligible for ITCs, followed by a similar review process as PTCs (e.g., construction date and evaluation of continuous construction).

A developer can demonstrate qualification for the Credits through an internal memorandum detailing the nature of the project’s eligibility, the date construction began, efforts undertaken to ensure continuous construction, and overall qualification for the Credits. A tax equity investor typically obtains a formal tax opinion regarding the project’s qualification for the Credits. However, these are not generally shared with a potential buyer of the developer’s equity interests.

A few other tax considerations to keep in mind as part of the overall transaction process:

- How will the purchase price be allocated for tax purposes (e.g., tangible property versus power purchase agreement)?

- Will your investor base include tax-exempt investors and, if so, does that impact your future tax depreciation benefit?

- Do you expect to perform a repowering during your hold period and, if so, will that result in a new ITC?

- Does the project company have a payment in lieu of tax agreement and how does that impact your financial model?

- Will the proposed transaction trigger a state and local transfer tax?

Conclusion

Tax due diligence and structuring related to renewable energy projects can be complex and an understanding of the nuances is critical. With the current political landscape and up-and-down history of renewable credits, the future of PTCs, ITCs, and potentially other tax-related incentives, is not easy to predict. One thing that will not change as long as the Credits and tax depreciation are shared with a Tax Equity Investor, tax due diligence and structuring will continue to play a major role in renewable investments for years to come.

[1] IRC § 45.

[2] Pub. L. 102 – 486, Title XIX (Oct. 24, 1992); Pub. L. 116 – 260, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (Dec. 27, 2020).

[3] IRC § 48.

[4] Pub. L. 109 – 58, Title XIII, Sec. 1301, Energy Policy Act of 2005 (Aug. 8, 2005).

[5] IRC § 45(a); IRC § 45(b)(2); BNA Portfolio 512-2nd: Tax incentives and Production and Conservation of Energy and Natural Resources, Working Papers, Worksheet 3 § 45, Renewable Electricity Production Credit Inflation Adjustment Factors, Reference Prices, and Credit Amounts.

[6] IRC § 45(b)(5).

[7] Notice 2013-29, 2013-20 I.R.B. 1085 (May 13, 2013).

[8] Notice 2021-5 on Beginning of Construction for Sections 45 and 48; Extension of Continuity Safe Harbor for Offshore Projects and Federal Land Projects.

[9] Notice 2020-41 (October 5, 2020).

[10] IRC § 48.

[11] IRC § 48(a)(5)(D).

[12] IRC §§ 48(a)(5)(E)-(F), 48(a)(6)-(7).

[13] IRC § 50(c)(1)

[14] IRC § 50(a)(1).

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] IRC § 50(a)(1)(B).