Retention in Market Cycles: Keeping the Talent Needed in Cyclical Industries

Every industry, at some point, will experience a downturn. Those companies that strategically plan for these events, foreseen or unforeseen, are more likely to survive and thrive in a difficult market. In some respects, all industries are cyclical, differentiated only in their severity and the duration of the cycles.

It is common for companies entering bankruptcy to implement retention programs for employees deemed critical to the organization’s survival through the bankruptcy process. These programs retain key talent, are approved by the bankruptcy judge, and provide security for creditors that the company’s number one asset, its people, remains in place. While this talent protection is discussed frequently in struggling companies, it is often overlooked in markets and industries on the uptick.

In companies that are thriving, it is common to see incentive programs that align pay and performance, but most companies do not consider “pay for retention” when industries are flush with cash and competitors are poaching critical talent. There are several key issues, techniques, and pay philosophies that companies should consider in rebounding or high-performing industries.

Retention

The key stakeholders that make corporate compensation program decisions, such as company ownership, compensation committees, and senior management teams, continue to receive strong external pressure from shareholders, proxy advisors like Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), and shareholder activists to link compensation programs to performance. This continued pressure has driven companies to create highly-levered incentive programs that are tied to, in some circumstances, ineffective or unnecessary performance metrics.

A critical part of any balanced compensation program is retention. In a highly competitive market for talent, strong stock price and incentive plan performance will not be enough to retain the talent needed to continue to differentiate your company in the market. High performers will exit for greener pastures if multiple layers of retention are not implemented. In these types of situations, the following compensation design features can be used to help alleviate some of the outside pressure to compete for talent:

- Cash retention bonuses – typically utilized below the executive level to provide six-to-twelve-month retention periods

- Multi-year incentive programs – incentive programs can be established for mid-level employees that provide incentives tied to long-term growth objectives (e.g., compound annual growth rates, “return on” metrics, business-unit-level operation metrics) that provide line-of-sight to long-term performance with multi-year cash payouts

- Restricted stock – for mid-level to senior-level employees, time- or performance-vested restricted stock or restricted stock units are an effective vehicle to retain employees while also aligning the interests of program participants with that of shareholders

- Deferred Compensation Programs – these low-cost programs can be designed for key employees with retention in mind while providing tax planning opportunities for participants

Non-Monetary Differentiation

While compensation is a key driver in employee behavior, it is not the only reason that many employees leave their organizations. Companies continue to come up with unique ideas to differentiate themselves from their competitors in stable markets. While many companies look to cut these programs in a market downturn, this can prove to be a costly mistake. The intent of these types of programs is to make employees’ lives easier, promote a company’s culture, and let employees know they are valued. Below are a few ideas that often get more “bang for the buck” in employee retention than typical cash-based compensation programs:

- Increased paid time off or “bonused” paid time off as a performance reward

- Increased paid maternity and paternity leave

- Paid for health promotion programs (gym memberships, on-site fitness classes, etc.)

- Flexible work hours or telecommuting

- Tuition reimbursement

- On-site concierge services (dry cleaning, vehicle wash/cleaning, massages, etc.)

- Raffles/giveaways (vacations, plane tickets, gift cards, event tickets, etc.)

- Team outings and social events

Pay-For-Performance – Changes to Section 162(m)

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (the “Tax Reform Act”) brought in sweeping changes to Internal Revenue Code section 162(m) (Section 162(m)), which historically provided a performance-based exception to the $1M limit on the deductibility of compensation paid to top executives of a publicly-listed company. Historically, if a public company provided compensation to their “covered employees” (which consisted of the Named Executive Officers excluding the Chief Financial Officer) in excess of $1M, the compensation in excess of the $1M limit would not be deductible by the company unless the compensation met the “qualified performance-based compensation” requirements of Section 162(m). With the passage of the Tax Reform Act, the performance-based exception has been eliminated, so all compensation earned by “covered employees,” now inclusive of the Chief Financial Officer, above the $1M limit can no longer be deducted by the public company. While Section 162(m) and the performance-based exception was historically a key consideration for most public company compensation committees, companies will now have different considerations in determining pay packages for the executives. A&M foresees the following impact to executive compensation programs going forward:

- Once a covered employee, always a covered employee – A “covered employee” will now be anyone who has ever served as Chief Executive Officer, Chief Financial Officer or one of the next three most highly compensated officers starting with 2017 covered employees. Companies will want to be careful to not inadvertently bump additional officers into the “covered employee” classification with one-off bonuses or stock grants, as they will always be subject to the $1M compensation deduction limit going forward. For acquisitive organizations acquiring another publicly-traded company, the acquired public company’s covered employees would also be considered covered employees of the acquirer going forward, which will further limit the surviving public company’s tax deduction.

- Positive discretion may be back – Under the previous terms of Section 162(m), a compensation committee was not allowed to exercise positive discretion to adjust payouts of performance incentive programs for fear of negating the deductibility of compensation over the $1M limit (negative discretion has always been permitted). With the removal of the performance-based exception, compensation committees may consider utilizing positive discretion within the company’s bonus and long-term incentive programs. Compensation committees may now consider differentiating themselves in the market by applying positive discretion in determining incentive payouts for select employees when performance metrics are not met (whether due to extenuating circumstances, or otherwise). While this may seem unreasonable to some shareholders and proxy advisors, and a strong disclosure justifying the decision may be needed, it provides the compensation committee with another useful tool when retention is critical in an ultra-competitive environment.

- Pay for performance is here to stay – Linking incentive programs to performance metrics is here for the foreseeable future, but companies and compensation committees may now be more flexible in their use of discretion and tolerance to make market-related adjustments to their incentive programs. It is typically a best practice to establish performance metrics with proper line-of-sight to participants and allow the full performance period to play out under the plan terms (set it and forget it!). However, in cyclical markets, there is frequently a need to make interim plan adjustments, positive or negative, to account for unforeseen circumstances. Without the constraints of Section 162(m), such adjustments can now be made.

- Companies with publicly-traded debt are now subject to Section 162(m) – One other important change to Section 162(m) under the Tax Reform Act is that now companies with publicly-traded debt are subject to Section 162(m), when they previously were not. While this may not impact many companies when compared to the number of public companies in the United States, these companies with publicly-traded debt will now be subject to the deduction limits of Section 162(m).

Create Sustainable Compensation Programs

With the U.S. financial crisis of 2008 and the energy market crash of 2015, thousands of employees lost their jobs and much of their retirement savings in these downturns. During these crises, it was near impossible to find employment for many displaced employees, while surviving companies retained the minimum number of employees required to keep operations afloat. Retention was critical during these times, but companies also used this time to “clean house” on bloated General & Administration expenses and establish a “new norm” for operations going forward.

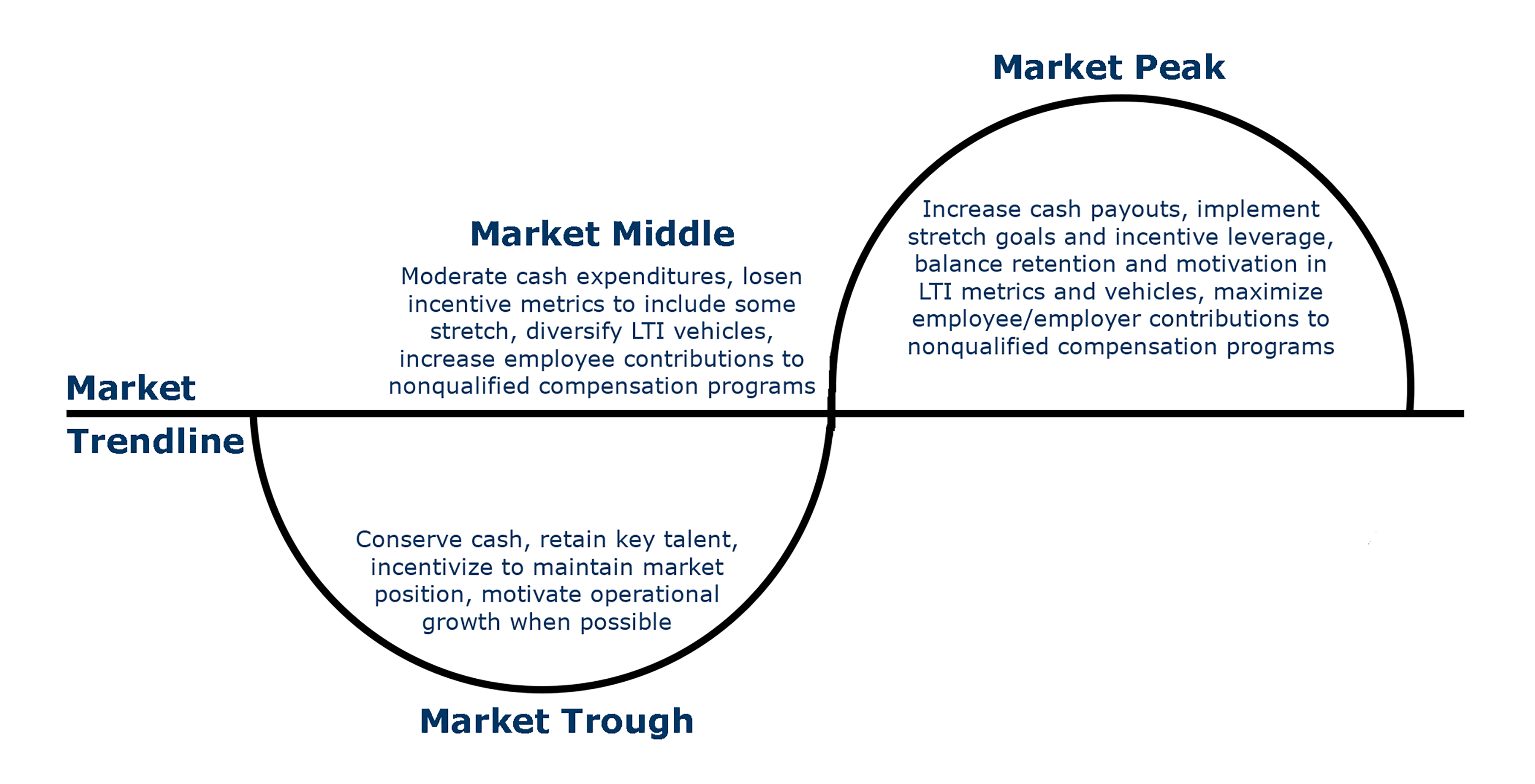

As markets rebound, companies tend to loosen their purse strings and quickly hire talent that may or may not be the right fit for the new environment. Retention in these environments is often overlooked because of the significant amount of wealth (incentives paying out at or near maximum, stock awards sharply increasing in value, etc.) that employees receive in a climbing market. However, if companies are not strategic in their hiring as well as their compensation program design, they will not be able to sustain or retain the critical talent they spent so much time hiring on the ride to the top. The following chart on market cycles displays typical attributes of compensation programs in market troughs, midpoints, and peaks. It is critical to understand what other companies are doing in these cycles to create customized and competitive compensation programs.

Establish a Compensation Philosophy and Stick to It

Most companies have a compensation philosophy, whether it is a stated formal policy or an informal philosophy, that is utilized to make compensation decisions. This philosophy many times is different at different levels in the organization and will evolve over time based on market factors, individual leadership influences, and internal factors. The key to an established compensation philosophy is to apply it consistently.

The concept of “buying” talent on the market when it is a critical position or required to support the company’s strategic initiative is valuable but should be used sparingly. There will always be competitors that may overpay to obtain a valued employee, but constantly chasing the market rather than sticking to the company’s compensation philosophy will only create problems over the long-term. Some attrition to overpaying competitors is healthy and should be expected. Using an established compensation philosophy as guardrails will ensure alignment with the compensation programs in place, allows the company to maximize budgets for the talent needed going forward and provides retention of the key talent in place.