Commissioner falls flat in PepsiCo High Court appeal… but on a steak knife’s edge

Summary

In an unlucky day for the Commissioner of Taxation (Commissioner), on 13 August 2025 the High Court of Australia (HCA) handed down its decision in Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc and Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc [2025] HCA 30. The HCA found in favour of PepsiCo, Inc (PepsiCo) in a narrow 4:3 majority, holding that there was no embedded royalty to which Australian royalty withholding tax (RWT) could apply, and that the diverted profits tax provisions (DPT) in Part IVA (Part IVA) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA 1936) had no application.

The HCA judgment was in respect of the appeal by the Commissioner against the findings of the Full Federal Court (FFC). The judgment of the FFC found in favour PepsiCo by a 2:1 majority, which was in turn an appeal of the earlier single judge Federal Court decision before Moshinsky J (who found in favour of the Commissioner). A&M’s analysis of the FFC decision can be found here, and our analysis of the first instance decision can be found here.[1]

While the decision may be touted by some as a ‘win’ for taxpayers, the implications of the HCA’s decision are far more nuanced, as the split in views at the HCA and FFC levels demonstrates.

Nevertheless, as the first judicial consideration of the DPT provisions in Part IVA, the HCA’s decision provides important commentary on their operation, and goes well beyond embedded royalties. In particular, the case provides helpful clarity on several broader issues, including:

- an authoritative position on income derivation;

- guidance on the use (and limits) of alternative postulates;

- insight into how the legislative factors in Part IVA should be weighed; and

- confirmation that the ‘do nothing’ counterfactual remains viable, at least in certain factual contexts, despite the 2013 amendments to Part IVA aimed at limiting its use.

However, the majority overtly emphasised the ‘unique’, arm’s length nature and longstanding context of PepsiCo’s arrangements, suggesting limits on the decision’s relevance in related-party scenarios. That emphasis also hints at how the Commissioner may continue deploying embedded royalty and DPT strategies where the facts differ.

Against this backdrop, multinational groups with cross-border arrangements involving intellectual property (IP) should remain alert to ongoing scrutiny from the Commissioner, and should consider reviewing their structures in light of this decision.

In Brief

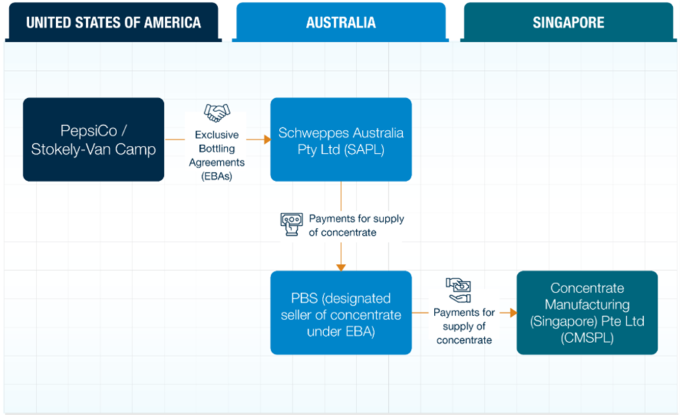

At the centre of the case were two exclusive bottling agreements (EBAs) separately entered into by PepsiCo and its subsidiary, Stokely-Van Camp, Inc (SVC) (both US resident entities) with Schweppes Australia Pty Ltd (SAPL), a third-party Australian resident distributor.

The Commissioner took the position that a portion of the payments made by SAPL to purchase concentrate from the PepsiCo-nominated related entity PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd (PBS) (which despite its name, was an Australian resident entity) should have been subject to RWT. This was on the basis that the payments included an embedded royalty component derived by non-residents PepsiCo and SVC for the use of PepsiCo and SVC's valuable trademarks and IP. Failing that and in the alternative, the Commissioner asserted that the DPT provisions in Part IVA applied to the tax benefit obtained from the arrangements.

The HCA majority (Gordon, Edelman, Steward, and Gleeson JJ) found:

- Payments by SAPL for concentrate were not, to any extent, ‘consideration for’ the use of IP and therefore did not include any embedded royalty. Instead, these payments were part of a ‘complex exchange of valuable promises’ between the parties.

- In addition, there was no royalty ‘derived by’ PepsiCo or SVC, as payments were made to PBS (an Australian resident). As such, no RWT liability could arise under section 128B(2B) of the ITAA 1936.

- DPT did not apply as the Commissioner’s counterfactuals were not ‘reasonable’ hence no tax benefit arose under section 177CB of the ITAA 1936.

The minority (Gageler CJ, Jagot, and Beech-Jones JJ) took a different view, finding that the payments by SAPL for concentrate did include an embedded royalty for the use of the IP. Upon construction of the agreements, the justices adopted the position that the interlocking series of exchanges of promises and grants of rights were part of a ‘single, integrated and indivisible transaction’ such that the payment for the concentrate, on an objective characterisation, must to some extent include a payment for the grants of the IP licences.[2]

However, the minority agreed with the majority that no RWT liability arose as the payments were not ‘derived by’ PepsiCo or SVC. On DPT, the minority disagreed with the majority judgment concluding that the requisite tax benefit and principal purpose existed such that the DPT did apply to the tax benefit obtained.

In terms of key takeaways:

- The decision will shape future interpretations of RWT, embedded royalties, DPT and Part IVA more broadly, especially in arrangements involving IP (e.g., software distribution).

- The majority’s detailed analysis will be a leading authority for future disputes under Australia’s general anti avoidance rules contained in Part IVA, including the Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL) and the DPT.

- The Commissioner’s guidance such as TR 2024/D1 - Income tax: royalties - character of payments in respect of software and intellectual property rights (TR 2024/D1) will likely need to be revised to reflect the HCA’s views, particularly on identifying the ‘purpose’ of a payment and the meaning of ‘consideration for’.

- While a clear win for PepsiCo, the majority judgment emphasised the ‘unique’ facts: independent parties, longstanding commercial relationships, no artificial restructuring to avoid RWT and the ‘complex exchange of valuable promises’ between the parties. This suggests that, unfortunately for taxpayers, this is far from the final word in the embedded royalty saga.

Case Facts

The Exclusive Bottling Agreements

As noted above, the case centred around EBAs entered into by PepsiCo (as owner of the Pepsi and Mountain Dew brands) and SVC (as owner of the Gatorade brand). These EBAs were entered into with SAPL, an unrelated Australian resident entity ultimately owned by Asahi Breweries, in its capacity as the ‘Bottler’.

The EBAs governed SAPL’s appointment as the exclusive distributor of PepsiCo and SVC's branded beverages in Australia. Under the EBAs:

- SAPL was appointed the sole and exclusive licensee to bottle, sell and distribute Pepsi, Mountain Dew and Gatorade beverages in Australia;

- PepsiCo (impliedly) and SVC (expressly) granted SAPL a licence to use their trademarks and other IP;

- The prices SAPL would pay per unit of concentrate required to manufacture the beverages were specified; and

- PBS was nominated by PepsiCo and SVC as the ‘Seller’ of the concentrate. PBS sourced the concentrate from Concentrate Manufacturing (Singapore) Pte Ltd and supplied it to SAPL.

Importantly, the EBAs did not provide for any separate royalty payment by SAPL for the use of the trademarks and/or any other IP.

The Commissioner’s Position

The Commissioner issued assessments seeking to impose RWT on the basis that a portion of the concentrate payments should have been characterised as a royalty. The Commissioner argued that, properly construed, the EBAs revealed that the payments were partly consideration for the use of PepsiCo and SVC’s valuable IP.

Alternatively, the Commissioner asserted that if the RWT provisions did not apply, the payments would be subject to the DPT provisions, a measure introduced into Part IVA of the ITAA 1936 in 2017. The Commissioner alleged that the taxpayers had a principal purpose of avoiding RWT and reducing their foreign tax liabilities, potentially exposing PepsiCo and SVC to DPT at a punitive 40% rate.

A&M Key Observations

The 93-page HCA decision brings the embedded royalty saga to an end for PepsiCo. However, the nuanced reasoning in the majority’s HCA judgment may limit the broader applicability of the decision.

Our key observations are set out below.

The terms of the contract and its substance matters

The HCA reaffirmed that commercial arrangements must be interpreted according to their actual terms and substance. The mere presence of a right to use IP does not automatically imply a royalty. Crucially, the majority’s judgment indicates it is not open to the Commissioner (or the courts) to recharacterise the parties’ agreed bargain or substitute an alternative commercial arrangement.

In particular, and on the evidence presented before the HCA:

- the majority found that while valuable IP rights were necessarily provided to SAPL to enable it to perform its obligations under the EBA, those rights were not provided ‘for nothing’;

- instead, the IP rights were part of a ‘complex exchange of valuable promises’ [3] between independent parties, and SAPL’s use of the IP brought benefits to PepsiCo and SVC; and

- as the ‘basis or condition for’ the concentrate payments was only the provision of the concentrate, there was no legal or economic reason – or basis – to attempt to bifurcate the concentrate payments to include an embedded royalty component.[4]

As succinctly put by the majority:

‘The Commissioner's argument ultimately depended on two related ideas: first, that PepsiCo and SVC had licensed SAPL to use the PepsiCo Intellectual Property; and second, that, unless part of the price SAPL paid to PBS for concentrate was a royalty paid to or derived by PepsiCo or SVC, SAPL obtained the licence to use the PepsiCo Intellectual Property for nothing. As these reasons will show, although SAPL did obtain a licence to use the PepsiCo Intellectual Property, no part of the price for the concentrate was payment for that licence. But SAPL did not obtain the licence for nothing. The right to use the PepsiCo Intellectual Property was part of a comprehensive commercial arrangement, an essential element of which obliged SAPL to build PepsiCo's and SVC's brands and strengthen the PepsiCo Intellectual Property. The more successful SAPL was, the more valuable the PepsiCo Intellectual Property became. SAPL's agreement to build the brands was of real value to PepsiCo and SVC. It was not "nothing". The Commissioner was wrong to assert that part of the arm's length price paid by SAPL to PBS for concentrate had to be treated as payment from SAPL to PepsiCo or SVC for the right of SAPL to use the PepsiCo Intellectual Property. There is no legal or economic reason to make that leap in logic. To do so would involve assigning part of the fair price paid for goods to a different commercial bargain. The Commissioner's appeals to this Court should be dismissed.’ [emphasis added] [5]

The majority’s refusal to make a ‘leap in logic’ to find an embedded royalty in this case is a welcome outcome, at least on these facts. Had the HCA accepted the Commissioner’s approach, it could have opened the door to increased scrutiny on a broad range of payments for embedded royalties.

That said, the 4:3 split and the HCA’s observations about the Commissioner’s lack of economic evidence suggest this result should not be seen as a blanket rejection of embedded royalty arguments. Rather, it highlights the importance of substantiating allegations or arrangements with clear legal and economic analysis (including IP valuation evidence) — a hurdle the Commissioner did not clear in this case.

To borrow from Steward J’s choice of words in the HCA hearing in April 2025, where a product is sold for consideration but the transaction also involves the provision of something else (e.g., in Steward J’s words - a set of steak knives) it is not necessary to apportion the consideration between the steak knives and the product, where the evidence does not support that. [6] Put another way, not every transaction involving the incidental provision of something else requires an apportionment of consideration.

The Commissioner will likely seek to distinguish PepsiCo’s facts when reviewing other taxpayers (e.g., where arrangements are less complex, of shorter standing, or involving related parties). Should this be the case, contractual drafting and contemporaneous evidence, including how consideration is determined and IP rights are valued, will be key to defend against attempts by the Commissioner to establish an embedded royalty.

Arm’s Length Dealings Matter

The independence of the parties and the longstanding nature of PepsiCo’s arrangements were central to the majority’s reasoning, and ultimately to PepsiCo’s success. This emphasis may narrow the decision’s direct applicability and relevance to related-party transactions.

At first glance, the HCA’s focus on contractual construction and the nature of the commercial bargain between parties might have offered broader, and much welcome, support for related-party models involving mutual exchanges of promises (e.g., marketing and brand-building efforts in addition to the mere purchase and supply of product).

However, any such optimism is tempered by the majority’s repeated and deliberate emphasis on the third-party, arm’s length nature of the PepsiCo arrangements, particularly in the DPT analysis, where the HCA described the scheme as a ‘product of arm’s length dealings between unrelated parties’. [7] This statement potentially limits the broader application of the judgment.

While related parties could, in theory, replicate similarly negotiated bargains, the majority’s focus on PepsiCo’s ‘unique facts’ arguably gives the Commissioner scope to challenge similar arrangements in non-arm’s length settings.

That said, and set out in further detail below, the ‘derivation’ issue may still present a significant hurdle for the Commissioner in future disputes involving separated IP licensing and product supply chains.

IP rights don’t equal royalty payments

As the majority judgment confirms, the existence of a right to use IP in a commercial arrangement does not necessitate the finding of a royalty payment. However, the judgment does not preclude the possibility that a payment for goods or services could be found to include a royalty component, particularly where there is evidence that the price paid is ‘inflated’ to reflect the value of any IP rights provided. In such cases, the Commissioner may suggest that RWT can still arise, provided the amount is derived by, or received under direction of, a non-resident.

This brings the ‘derivation’ point into sharp focus. Significantly, this point was the only one on which all seven HCA justices and all three FFC justices agreed (with only Moshinsky J at first instance finding that the payments had been derived by PepsiCo and SVC). In concluding that PepsiCo and SVC did not derive the payments, the majority of the HCA again focussed on the proper construction of the relevant contractual arrangements which, once PepsiCo had nominated PBS as the seller of concentrate, did not impose any obligation on SAPL to pay PepsiCo or SVC (whether actually or constructively).

Because the concentrate payments were made to an Australian resident PBS, and were not found to have been paid to, or dealt with at the direction of PepsiCo or SVC, no RWT liability could arise, even if the payments had included an embedded royalty.[8]

The lack of derivation was a crucial weakness for the Commissioner on the PepsiCo facts and may also be a significant stumbling block in any future attempts to impose RWT on an embedded royalty (particularly where the payment recipient is not the owner of relevant IP).

The near uniform conclusions on the derivation point (at all court levels) also carry broader implications. For example, in the context of interest withholding tax (which is subject to the same ‘derivation’ and deemed payment rules), and for various other provisions in the tax law where derivation is a threshold requirement.

DPT and Part IVA Counterfactuals

The HCA majority made clear that constructing a valid counterfactual requires more than hypothetical tax-saving comparisons. A critical factor in PepsiCo’s success was its ability to demonstrate that no other reasonable commercial alternatives existed, though the majority carefully emphasised that the conclusion rested on ‘critical facts, unique to these appeals’.[9]

In what is likely to become a seminal authority on Part IVA counterfactuals (particularly post-2013 Part IVA amendments), the majority clarified several important principles:

- The taxpayer bears the onus of proving there is no tax benefit.

- Merely proving that the Commissioner’s alternative postulates are not reasonable is not enough to satisfy that onus of proof.

- A taxpayer does not need to prove the existence of a reasonable alternative postulate that avoids tax.

- An alternative postulate must be based on a reasonable expectation which is ‘more than a possibility’ (citing FCT v Peabody (1994) 181 CLR 359 at 385.)[10]

- Despite the 2013 amendments to Part IVA being intended to prevent the simple reliance on the non-existence of the scheme (i.e., the ‘do nothing’ postulate), a taxpayer can still rely on that position in ‘unusual cases’. As always, how the relevant scheme is defined will be important to the assessment of whether there are reasonable alternative postulates.[11]

- The economic and commercial substance of the scheme remains central to assessing the reasonableness of any alternative postulate.

The question of what is a reasonable alternative postulate is a consistent theme across other recent decisions, including a string of recent Part IVA defeats for the Commissioner. For example, in Mylan [12], Button J ultimately found that the Commissioner’s primary alternate postulate did not represent a prediction of the events which might reasonably have taken place, with the Federal Court presenting and applying its own alternative postulate (but ultimately finding no dominant purpose). Our insights on the Mylan case can be found here.[13]

In PepsiCo, the majority found that the true economic and commercial substance of the scheme was that the price agreed for the concentrate was solely for the concentrate, and nothing else. The longstanding franchise arrangements and the surrounding commercial context enabled PepsiCo to establish that ‘it was probable that no different arrangement might reasonably be expected to have been entered into’.[14]

Notably and somewhat surprisingly, the majority in PepsiCo appears to have revived the ‘do nothing’ counterfactual, despite the Commissioner’s position that the 2013 amendments to Part IVA had effectively ruled it out. While the majority accepted it remains available in limited cases, a key question for future avoidance cases will be how 'unusual' a case must be for a taxpayer to prove that there is ‘no reasonable alternative' in order to apply a ‘do nothing’ counterfactual.

Principal and dominant purpose tests

Given the conclusions reached about the lack of reasonable alternative postulates and therefore lack of a ‘tax benefit’, the majority did not need to address the question of principal purpose; but nevertheless chose to provide some important guidance.

Although the case considers the DPT, that guidance will have wide application for future disputes beyond DPT, including the MAAL and ‘general’ Part IVA. This was admitted by the Commissioner in his special leave application.

In particular, despite the parties’ submissions on purpose primarily focussing on only two factors - being the manner of entry into the scheme (section 177D(2)(a)) and the form and substance of the scheme (section 177D(2)(b)) - the majority made an effort to step through each of the 11 legislative DPT factors. The majority also made a clear finding as to whether each factor supported (or did not support) a principal purpose of obtaining a tax benefit, an approach which departs from the more common practice of finding that some factors are ‘neutral’ (a practice adopted by the lower courts in this case).

More specifically and in looking at the ‘manner in which the Scheme was entered into or carried out’:

- The majority drew on some of the HCA’s classic Part IVA judgments (the cases of Spotless and Hart) to reiterate the position that a relevant purpose is not necessarily found just because a taxpayer takes tax considerations into account. They noted that ‘it would be unthinkable to suppose that sophisticated commercial operators did not take tax outcomes into consideration in negotiating the form of a transaction’, referencing ‘the choice of leasing rather than buying business premises’ as described in Hart’s case as ‘illustrating that reality’.[15]

- This is consistent with recent Part IVA cases, including the 2024 FFC decision in Minerva in which it was held that just because a taxpayer ‘desires’ a tax benefit or even chooses between two transactions based on tax considerations, this does not equate to establishing a dominant purpose of obtaining a tax benefit. A&M’s analysis on the Minerva decision can be found here. [16]

- It was also of significant weight that the scheme was the product of arm's length negotiations between ‘experienced and large commercial enterprises’ and that the scheme produced a price payable for concentrate that was not shown to be disproportionately high and which was paid to an Australian resident taxpayer.

- Finally, the fact that the EBA followed a longstanding, pre-existing and ‘entirely commercial way of doing business’ (being the longstanding franchising model employed by PepsiCo and its predecessor for over 100 years) was clearly in PepsiCo’s favour. [17]

In looking at the ‘form and substance’ of the scheme, the majority repeated its findings (relevant to the question of ‘tax benefit’) that ‘the price agreed for concentrate was for concentrate’ meant there was alignment between ‘form and substance’.[18]

In addition, the majority made some interesting comments in relation to section 177D(2)(d) – being ‘the Australian tax result that would be achieved but for the application of Part IVA’. The majority accepted PepsiCo’s evidence that the RWT said to be avoided represented about one per cent of total payments made by SAPL and therefore represented a ‘negligible sum for such large commercial enterprises’. It found that this factor ‘militates strongly against the presence of the required principal purpose’. [19] It is particularly noteworthy that the Commissioner did not lead any evidence around this pricing point.

Apart from the final legislative factor considered (in respect of which PepsiCo conceded in the lower courts that for the purposes of section 177J(1)(b) the arrangements had resulted in a reduction in United States tax), all factors were found by the majority to be in PepsiCo’s favour. As such, the existence of tax savings alone was of limited weight and not sufficient to establish a principal purpose of obtaining a tax benefit under the multi-factorial principal purpose test.

This will be influential for Part IVA cases more generally, particularly once Part IVA is expanded to capture schemes that achieve an Australian income tax benefit, even where the dominant purpose is to reduce foreign income tax.[20]

Impact on ATO Guidance

The finalisation of draft TR 2024/D1 was deferred by the Commissioner pending the outcome of this case. Following the HCA decision, the Commissioner issued a public statement acknowledging the decision [21], confirming that broader implications are being considered.

It is likely that TR 2024/D1 (and any future guidance) will require reworking to reflect the HCA’s views on contractual construction, derivation and interpretation of relevant concepts including the meaning of ‘consideration for’, particularly in the context of software arrangements. Given such arrangements typically occur between related parties (as distinct from the facts PepsiCo), it will be interesting to see how the Commissioner applies the HCA’s views in related-party software distribution contexts.

The recently released Draft PCG 2025/D4 - Low-risk payments relating to software arrangements - ATO compliance approach (PCG 2025/D4) appears less likely to be materially impacted by the case, subject to any flow-on from a revised TR 2024/D1. That said, certain definitional aspects may need refining. For example, the current definition of ‘undissected payments’ in paragraph 11 does not contemplate scenarios where royalty-related IP rights are addressed in a separate legal agreement from the main software contract. In light of the majority’s reasoning, it would be timely for the Commissioner to consider updating PCG 2025/D4 to include additional examples across a broader range of ‘risk zones’, beyond the current white and green zones.

Another piece of ATO guidance to keep front of mind following the judgment is PCG 2024/1 – Intangibles migration arrangements (PCG 2024/1). While PCG 2024/1 explicitly excludes analysis of embedded royalties and related RWT issues, it provides a risk assessment framework for evaluating the likelihood that the Commissioner will apply Part IVA, DPT, or the transfer pricing provisions to cross-border related party arrangements involving intangibles ‘migration’.

‘Migration’ is defined broadly and captures situations where Australian activities connected to IP are either mischaracterised or not properly recognised or compensated. In the context of PepsiCo, had SAPL been a related party, its local bottling operations could have triggered scrutiny under PCG 2024/1, particularly if they involved development, enhancement, maintenance or protection (DEMP) of offshore held IP, or local development of IP subsequently exploited offshore.

The Commissioner is likely to continue using PCG 2024/1 as a risk assessment and enforcement tool for related-party arrangements involving intangibles, especially given the majority’s repeated emphasis on SAPL’s third party, arm’s length status in reaching their decision.[22]

The PepsiCo decision reinforces the importance of robust documentation, not only legal agreements but also contemporaneous records that demonstrate the rationale for key commercial decisions and valuation and pricing.

Going forward

While the decision is clearly a win for PepsiCo, the unique facts of the case and the deliberate nuances in the majority’s judgment suggest that, unfortunately for taxpayers, this is far from the final word on the embedded royalty saga.

To the contrary, the majority judgment suggests the justices readily understood the considerable precedential weight of their judgment. Despite the Commissioner’s defeat in this case, we expect continued scrutiny of arrangements involving intangibles that differ from the facts in this case, with a focus on identifying whether the pricing of goods or services may include an embedded royalty component, particularly where:

- The arrangements are between related parties;

- The arrangements have not been in place for extended periods;

- The supply of goods/services/rights and the provision of IP rights are from the same entity; or

- It can be demonstrated that the price paid for the goods/services/rights was inflated ‘to hide some secret royalty outlay’.’[23]

A Decision Impact Statement will follow from the Commissioner, though it may take some time. In the meantime, taxpayers should assess the robustness of existing structures and operating models, particularly in light of growing scrutiny under the evolving global tax landscape, including the United States’ One Big Beautiful Bill Act reforms, tariff increases and uncertainty and, of course, the implications of Pillar Two.

With regard to documentation, appropriate pricing and substantiating economic evidence will remain key to managing the risk of challenge on similar arrangements. This will be even more relevant to ‘significant global entities’ with the introduction of new penalties for the mischaracterisation or undervaluing of royalty payments which would otherwise be subject to RWT, as announced in the 2024/2025 Federal Budget. [24]

[1] An analysis of Pepsi’s tax case in Australia: A look at ‘embedded royalties’ and diverted profits tax, April 2, 2024, https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/analysis-pepsis-tax-case-australia-case-study-embedded-royalties-and-diverted-profits-tax; PepsiCo, Inc v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCAFC 86 - Another chapter in the embedded royalties saga, August 14, 2024, https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/pepsico-inc-v-commissioner-taxation-2024-fcafc-86-another-chapter-embedded-royalties-saga

[2] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 59

[3] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 166

[4] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 166

[5] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 123

[6] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA Trans 23

[7] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 219

[8] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 185. This is because section 128B(2B) of the ITAA 1936 broadly requires that the royalty be ‘derived’ by a relevant non-resident, and by virtue of the legislative definition of royalty in subsection 6(1) and the deemed payment rule in section 128A(2) of the ITAA 1936, includes royalties which are ‘dealt with on behalf of the other person or as the other person directs.’

[9] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 219

[10] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 219

[11] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 212

[12] Mylan Australia Holding Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (No 2) [2024] FCA 253.

[13] Mylan Australia Holding Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation – Part IVA ruled not to apply to debt push-down, April 14, 2024, https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/mylan-australia-holding-pty-ltd-v-commissioner-taxation-part-iva-ruled-not-apply-debt-push

[14] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 224

[15] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 229

[16] Minerva Financial Group Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCAFC 28. Analysis of Recent Full Federal Court Decision in Australian Tax Case. April 8, 2024, https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/analysis-recent-full-federal-court-decision-australian-tax-case

[17] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 230

[18] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 232

[19] Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 233

[20] These amendments are proposed to apply from 1 July 2024. Australian Federal Government, Budget 2023/2024, Budget Measures, Budget Paper No. 2, Budget Paper No. 2: Budget Measures

[21] Australian Taxation Office, High Court decision in Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc, 13 August 2025, https://www.ato.gov.au/media-centre/high-court-decision-in-commissioner-of-taxation-v-pepsico-inc

[22] Appendix 1 of PCG 2024/1 outlines 15 illustrative IP scenarios, underscoring the breadth of its intended application. Appendix 2 sets out the Commissioner’s evidentiary expectations for supporting the commerciality and arm’s length nature of intangible arrangements.

[23] The majority observed that the Commissioner did not, in PepsiCo, contend that the prices were incorrect or had been inflated to hide some secret royalty outlay. Commissioner of Taxation v PepsiCo, Inc.; Commissioner of Taxation v Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. [2025] HCA 30, Paragraph 167.

[24] Australian Federal Government, Budget 2024/2025, Budget Measures, Budget Paper No 2, https://archive.budget.gov.au/2024-25/bp2/download/bp2_2024-25.pdf, See our summary of this measure in our 2024/2025 budget update here.