Real Estate & Border-Adjustable Tax Reform: A BAT Out of Nowhere?

Almost five months have passed since the presidential election, and conversations are increasingly shifting to the looming promise the House Republicans made to issue an overhauled tax code during the 2017 year. Once it became clear that Washington would have congruency in political party majority in both the White House and both chambers of Congress, tax reform quickly became a hotly discussed topic. Renewed attention was brought to the tax reform “Blueprint” issued by House Republicans early last summer.

Let’s be clear, the uncertainty is still there — as much as the various components of suggested tax reform have been discussed, it is still, in fact, in its very early stages, and the final details, manner and timing of implementation all remain up in the air. But words of confidence continue to be relayed to taxpayers by House Republicans, with House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), who is spearheading the House effort along with House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady (R-Texas), recently telling reporters “we’re going to get tax reform done” — albeit admitting to the prevailing uncertainties, stating “there’s going to be a whole bunch of drama” to be reported between now and then. Early discussions of timeline suggested mid-2017, with the latest forecasts being pushed back to late 2017 or even 2018 depending on which Republican representative you’re talking to (noting that numerous Republican senators remain pessimistic about certain key aspects of the House Republican Blueprint, while many Democratic representatives don’t think major tax reform will be passed at all).

Much of the initial (and continued) focus surrounded the treatment of certain common items, such as tax rate reform, depreciation and interest expense deductions. The uncertainty remains surrounding these items, especially concerning the real estate industry. Conversations have ranged from the applicable rate of tax on rental real estate income, including carried interest, to whether current levels of property financing will continue to be justified in the capital stack of future acquisitions. Throw into this mixed bag the impact of immediate expensing of capital expenses, and you have a venerable list of topics to consider for the future of your real estate portfolios. And we won’t even mention the complexity of the unknown transition rules, the potential doing-away of IRC Section 1031 exchanges and/or a potential full repeal of the estate tax.

But there’s one more thing…

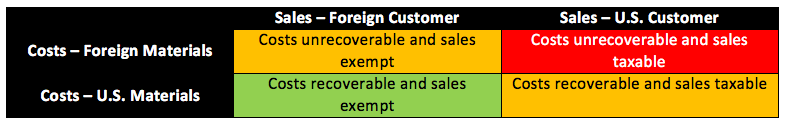

Included as part of the Blueprint, and definitely a topic that was quickly noticed upon its initial release, is the notion of effectively transforming the current U.S. worldwide taxation of business income into a border-adjusted, destination-based cash-flow tax system. In basic terms, the move would be to a system that most favors companies that manufacture their products within the U.S. and sell them overseas, while most heavily taxing companies that import their materials and sell the finished products domestically. This would be achieved through some combination of excluding gross receipts associated with sales to foreign customers (and including those associated with sales to domestic customers) and deducting cost recovery of the materials associated with goods acquired from U.S. customers (and disallowing those associated with goods acquired from foreign customers).

The most immediate issue with this so far, much like the other aspects of tax reform, is the lack of guidance or any detail beyond this basic concept, all in the face of the House Republicans’ promise of finishing tax reform this year. Most of the discussion has been in terms of the corporate tax structure, calling the “BAT” (border-adjustment tax) a 20 percent tax on imports — the new tax rate imposed on corporations under the Blueprint.

But what about pass-through entities, such as S-corporations, partnerships and REITs? What about the fact that much of the business income generated in real estate is through the rental of existing immovable property (both U.S. and foreign) and not always the “manufacturing” of new property in order to generate a “sale”? And while we’re on the topic, what about those times that the real estate product is manufactured to generate a sale, such as homebuilding and condominium construction?

When Apple arranges for the manufacture of iPhones at Foxconn’s site in Taiwan, it is easily evident that the glossy devices being sent over in their neat little boxes, to be sold in one of its many retail stores in the U.S., would probably be considered an imported good under the suggested Blueprint. But Apple probably arranged for this because the cost to manufacture its iPhone this way is more cost-efficient than manufacturing it domestically (ignoring potential tax impacts under the Blueprint). However, when a real estate developer decides to use certain premium foreign materials, many times it is because the material simply isn’t available here. One cannot get Italian marble, and its accompanying quality, domestically. The same may be said for various types of stone, tile and glass.

The border-adjusted tax approach would suggest the homebuilder or condominium developer would receive zero cost recovery benefit to the extent such imported materials are used — which can add up to be a pretty penny if we’re talking about a luxury tower in San Francisco or midtown Manhattan. Further, these materials are usually imported due to the desire of the ultimate consumer for a high-grade material — not because of the developer attempting to streamline its costs.

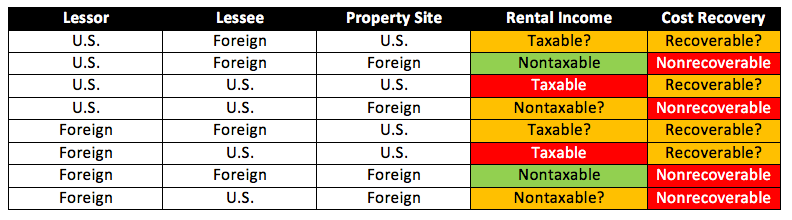

Rental real estate finds itself in a similar quandary. The impact of border-adjustability to lessors of real estate presents a few questions. What is considered “consumption” in terms of real estate? Is it the tax situs of the consumer/lessee (in which case lease income related to a foreign lessee may be exempt from taxation in some cases)? Or is it the tax situs of the actual property, in other words, where the property’s consumption is occurring (in which case, lease income from U.S. property would always be subject to taxation, regardless of the foreign or domestic status of the lessee)? Furthermore, rental real estate companies quite frequently purchase pre-existing properties from other sellers. Manufacturing or construction activity is many times not connected with a business strategy involving income from rental activity. To what extent is an acquirer of real property responsible for determining the source of the underlying materials for purposes of justifying a deduction for depreciation (or to justify the immediate deduction of the entire acquisition, under the Blueprint)? If we assume the border-adjustment rules are effective only for construction of new real estate, does this mean only the initial builder of the real estate would be subject to these rules for purposes of cost recovery — and that subsequent resellers of the same property would be able to enjoy cost recovery for tax purposes? Or would the “import taint” stay with the property in perpetuity?

The tables below attempt to bring a breath of fresh logic to the questions raised by the border-adjusted tax approach to real estate. Uncertainty abounds:

Construction/Manufacturing Activity

Rental Activity

The industry is still trying to wrap its mind around the impacts of which tax rates would apply to rental real estate businesses conducted through pass-through entities (the 16.5 percent tax on passive income, the 25 percent tax on pass-through business income and the 33 percent tax on “other” income), the disallowance of net financing costs, and the immediate expensing of capital expenditures — issues that are central to the economics of forming a deal. The increased spotlight on the impact of border adjustment creates an even larger “overarching” cloud over being able to evaluate the impacts of these other items, as cost recovery and taxability of gross rental receipts are key items that drive the after-tax return on investment for a given investor.

Recent discussion surrounding the pros and cons of border adjustability has also suggested that the impact of the rules on the value of the U.S. dollar must be taken into account in evaluating the net merits of the system. In a core manufacturing world, specifically one where the goods historically manufactured overseas can actually be manufactured in the U.S., the argument is the reduced U.S. taxes on exports would pass to foreign consumers as savings in product price, creating more demand for these products overseas and, in turn, more demand for the U.S. dollar. Taxing imports would reduce U.S. demand for them, meaning fewer dollars would travel overseas, reducing the supply of the dollar in the worldwide system, thereby increasing its value.

If this theoretical, macroeconomic movement in currency value actually occurs, its impact may be yet another head-scratcher for the real estate industry. If gross rental income is taxed by defining “consumption” location as the tax situs of the actual real property (versus that of the lessee), then a lessor of U.S. real estate doesn’t have much to look forward to in terms of this “export” benefit. In fact, the foreign lessee may also be less apt to sign a lease payable in U.S. dollars if the value of the dollar does indeed increase against the home currency of the foreign lessee.

Within the past month, the Senate has recently voiced its concerns about the BAT system; Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) went so far as to say he doesn’t “see [the border-adjustment plan] happening, not the way the House has configured it.” Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) expects the Ryan-Brady tax reform plan “won’t get 10 votes in the Senate.”

However, what has so far been an almost-absent factor, the Trump administration is expected to roll out its comprehensive tax plan within the coming weeks. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin commented that work has been happening closely “with the leadership in the House and the Senate” and that a “combined plan” is also a strong possibility. Specific to the border-adjustability portion of reform, Mnuchin did say that while there are some concerns about it, “there’s some interesting aspects of it.” Perhaps most poignant is President Trump’s recent comments that the border-adjustability tax “could lead to a lot more jobs in the United States.” Regardless, some much-needed clarity on border-adjustability is probable to surface once the Trump administration announces its tax plan within the next month.

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand Says:

With fewer inherent business variables in real estate development, discussions may need to begin among procurement and architectural planning departments in order to think through the implications of cost recovery for tax purposes. The business model lends itself to being easily analyzed under a “cost of goods sold” approach, and therefore we think some level of a border-adjusted tax system, if enacted, will apply to these industries. Although a single-family home community of 1,000 homes or a condominium tower of 500 units may sound large, the unit numbers pale in comparison to how many cars are sold by an automaker or how many televisions are sold by a manufacturer. Therefore, the impact of such reform on a company in this line of business can be significant on the level of each transaction. Conversely, modeling the impact of a border-adjusted tax system on a real estate business may also prove to be relatively more accurate and beneficial.

The rental market has quite a bit of uncertainty under a BAT system, at least with the current level of information available. However, it would be prudent for developers of properties for a rental business model to consider the potential impact material-sourcing rules could have on their holding periods, expected internal rates of return, leasing structures and exit strategies for their investments. These considerations should go hand-in-hand with the impacts of the other, more probable, reform proposals out there concerning carried interest, financing costs and capital expenditure expensing. For existing rental projects, protective language in lease agreements may also be considered to ensure the future revenue stream of a portfolio asset is not overburdened by tax reform enacted subsequent to the lease. Flexible rent escalation clauses may provide lessors some top-line cushion. Furthermore, a closer look at tenant improvement allowances may be advantageous based on the expected sourcing of materials used for future improvements. In any event, players in this market would be well advised to keep watch for further developments.