Potential Traps for Non-U.S. Based Multinationals Under the New Tainted Transaction Rules of the 385 Regulations

Many companies breathed a sigh of relief at the release of temporary and final regulations under Internal Revenue Code Section 385 on October 13, 2016. The final regulations severely limit the scope of the previously proposed regulations, which were issued on April 3, 2016. Most notably, the final regulations do not apply (yet) to debt issued by foreign companies, as the final regulations reserve on foreign issuers. Thus, for the time being, the final regulations apply only to debt issued by U.S. companies. This change greatly limits the applicability of these regulations to U.S. based multinational organizations. Unfortunately, this limitation is of little to no help to non-U.S. based multinationals with U.S. subsidiaries.

This edition of Tax Advisor Weekly provides an overview of the so-called “tainted transaction” rules of Final Regulation Section 1.385-3, including the controversial funding rule. This article also discusses some potential traps for non-U.S. based multinationals with U.S. subsidiaries under these rules. Additionally, this article discusses the recharge exemption that was introduced in the final regulations and may be used to introduce debt into the U.S.

It is important to note that there is considerable speculation that the upcoming Trump Administration may eliminate the final regulations. That being said, the portions of the final regulations dealing with certain tainted transactions are currently in effect. The final regulations also include certain documentation requirements that do not take effect until January 1, 2018. For that reason, in light of the recent change in political landscape, this article does not discuss the documentation rules.

What’s at Stake in a Debt Versus Equity Controversy

The 385 regulations provide the IRS with another arrow in its quiver when it comes to reclassifying related-party debt as equity. Under pre-existing U.S. case law, which historically controlled debt versus equity analysis, a facts and circumstances test based largely on the intent of the parties, borrowing capacity of the debtor and other factors applied to determine whether a purported debt instrument should be recast as equity.

When a debt instrument between related parties is reclassified as equity, it can give rise to various adverse U.S. tax consequences. These include but are not limited to:

- Loss of U.S. interest deductions. This can give rise to additional U.S. income tax, both historical and prospective, as well as IRS interest and penalties if interest deductions from a prior year are disallowed.

- U.S. withholding tax on deemed and future dividend payments. When a debt instrument is reclassified as equity, payments of interest and principal are reclassified as dividend payments, which typically carry a higher rate of U.S. withholding tax under treaties. Additionally, penalties and interest may be charged by the IRS for non-payment of U.S. withholding taxes if interest payments from prior years are reclassified as dividends.

The Tainted Transaction Rules

The final regulations solidify the tainted transaction rules under which certain related-party debt that would otherwise be respected as debt under pre-existing case law will now be automatically recast as stock, regardless of the borrowing capacity of the debtor. Note that these rules were put in place with the proposed 385 regulations that were issued in April but have been modified in several areas by the final regulations.

The General Rule

A debt instrument issued by a domestic corporation to a foreign corporation that is part of the same “expanded group” (which may be loosely defined as a group of corporations that are 80 percent or more owned, directly or indirectly, by a common parent corporation) is automatically recast as stock (i.e., regardless of the reason for the issuance and regardless of the borrowing capacity of the issuer) if it is issued in any of the following transactions absence the application of one of the enumerated exceptions in the 385 regulations:

- In a distribution (e.g., a dividend);

- In exchange for stock of a member of the expanded group; or

- In exchange for assets of a member of the expanded group in a transaction, which is considered a “reorganization” under U.S. tax law.

The general rule makes it difficult for a U.S. company to issue debt to a foreign related party in a “cashless” transaction, such as where the U.S. company issues debt for no consideration at all or for consideration that simply amounts to the reshuffling of group companies with no real change to the group as a whole. This concept is discussed in more detail below.

The Funding Rule

A debt instrument issued by a domestic corporation to a foreign corporation that is part of the same “expanded group” is automatically recast as stock (i.e., regardless of the reason for the issuance and regardless of the borrowing capacity of the issuer) if it is issued in exchange for property (including cash) and within 36 months before or after the issuance the issuer enters into any of the following transactions (absent the application of one of the enumerated exceptions in the final regulations):

- A distribution to a member of the expanded group (e.g., a dividend);

- An acquisition of stock of a member of the expanded group; or

- An acquisition of substantially all the assets of a member of the expanded group.

Treasury realized that companies could attempt to circumvent the general rule by having a U.S. company issue debt in exchange for cash or other property and then in a separate transaction undertake one of the tainted transactions listed in the general rule. Thus, consistent with the proposed regulations, the final regulations adopt a 72-month rolling window that is meant to alleviate this concern. This concept is discussed in more detail below.

Potential Traps

What follows is a discussion of some traps that these new rules may create for non-U.S. based multinationals with U.S. subsidiaries. It is important to note that although the new related-party loan documentation rules do not apply to debt issued prior to January 1, 2018, the tainted transaction rules, including the funding rule, apply to certain intercompany debt issued on or after April 4, 2016.

Additionally, there are several exceptions to the general rule and the funding rule. Based on our experience working through these exceptions with several clients, we have found that they tend to be very fact specific. Thus, their applicability to a given situation is largely based on the tax attributes and other circumstances of a company. An in-depth discussion of the exceptions is beyond the scope of this article. We will instead focus on the general concepts under the final regulations.

Trap #1: Overcapitalized/Underleveraged U.S. Subsidiary

When a non-U.S. based multinational establishes a U.S. subsidiary, it often capitalizes the new entity with a mixture of debt and equity. This form of capitalization continues to be a viable transaction under the 385 regulations. However, please note that the historic principles of debt versus equity analysis under pre-existing U.S. case law and IRC 385 continue to apply. Additionally, for transactions that occur after January 1, 2018, the new documentation requirements must be fulfilled, and it may be prudent to follow these documentation regulations for debt that is issued today.

Once the initial capitalization of a U.S. subsidiary is in place, the U.S. Treasury Department does not believe that U.S. subsidiaries of non-U.S. based multinationals should be permitted to recapitalize, converting existing equity into interest-bearing debt. This is largely prevented by the tainted transaction rules. For example, historically a U.S. subsidiary of foreign parent could distribute its own promissory note to its foreign parent. If the tax attributes and facts aligned correctly, this could be achieved with no adverse U.S. tax consequences. The result of this transaction was that new intercompany debt was created without the necessity for the foreign parent to put cash into the U.S. subsidiary (i.e., a cashless transaction). This transaction was used for many years and by many non-U.S. based multinational groups (including many so-called inverted groups) in recapitalization transactions.

Under the final regulations, this transaction no longer gives rise to interest-bearing debt. Absent an exception to the general rule, the note distributed by the U.S. subsidiary will be reclassified as stock, giving rise to the potential adverse U.S. tax consequences discussed above. Thus, in order to push more debt into the U.S. subsidiary, the foreign parent must put more cash into the U.S. (in the absence of some other exception from the tainted transaction rules). This result may be unsatisfactory for U.S. subsidiaries that are overcapitalized/underleveraged and merely wish to recapitalize.

Trap #2: U.S. Subsidiary with Related-Party Debt Pays a Dividend to Foreign Parent

Under the funding rule, if within 36 months before or after a dividend is paid by a U.S. subsidiary to its foreign parent, the U.S. subsidiary has issued debt to a member of its expanded affiliated group, that liability is automatically recast as stock (i.e., regardless of the reason for the loan and regardless of the borrowing capacity of the U.S. subsidiary) unless an exception applies.

For example, if in year one a U.S. subsidiary borrows money from a foreign related party to fund working capital (which is permissible under the 385 regulations), then pays a dividend to its foreign parent company as much as 36 months after the debt issuance, the debt is automatically reclassified as equity on the date of the dividend up to the amount of the dividend unless an exception applies.

This trap is very difficult to deal with. We recommend that when paying dividends or issuing related-party debt from a U.S. company to a foreign related party that the 6-year timeframe surrounding the transaction be carefully examined to determine whether it may be tainted by another transaction occurring during that period under the funding rule. Additionally, if your U.S. subsidiary makes recurring dividend payments to its foreign parent, it may be difficult to have your U.S. subsidiary issue debt to a foreign related party.

One way to avoid a potential reclassification of the debt as equity under these rules is to consider paying off principal on an existing loan, in lieu of paying a dividend. This allows for the U.S. subsidiary and foreign parent to control the tax consequences of their transaction. It may also allow the U.S. subsidiary to incur further debt to foreign related parties without running afoul of the funding rule. Admittedly, paying off debt will also reduce the tax shield in the U.S. that the interest payments provide. That being said, if the debt is reclassified as equity, that would happen anyway. If principal is repaid, you will be able to control the tax treatment of the repatriation.

Trap #3: Transactions Unrelated to the Original Debt Issuance May Cause Equity Reclassification

Application of the final regulations, specifically the funding rule, may cause transactions that are totally unrelated to an original debt issuance by a U.S. company to a foreign related party to cause the debt to be reclassified as equity. Below is an illustration of how this may be possible:

In the above illustration, assume that U.S. Sub 1 issues debt to Foreign FinCo in year one in exchange for cash (e.g., to fund its working capital needs). Then, two-and-a-half years later (30 months), the multinational group decides that it no longer wishes to have two U.S. entities. So, pursuant to a legal reorganization totally unrelated to the original debt issuance, U.S. Sub 1 buys U.S. Sub 2 from Foreign Sub 2 for cash. U.S. Sub 2 then liquidates or merges into U.S. Sub 1.

This is a very common transaction that is often driven by legal and operational considerations (the U.S. tax considerations are often secondary in these transactions as they are often immaterial). This fact notwithstanding, as the original loan was issued less than 36 months prior to the acquisition of U.S. Sub 2 by U.S. Sub 1, the funding rule would cause the original debt to be reclassified as equity at the time of the asset reorganization in an amount up to the purchase price paid by U.S. Sub 1. Note that there may be applicable exceptions to this reclassification that could be used.

This seems like a very unfair result considering the fact that the second transaction described above was driven by legal and operational considerations and not tax. This serves as an illustration of how these rules can take a seemingly innocuous transaction and create adverse U.S. tax consequences under the final regulations. Treasury explained in the preamble that the reason for including related-party stock and asset transfers in the tainted transaction rule is that these types of transactions, if not included, would provide an easy way around a rule that applies only to dividend distributions, the thought being that payments of cash in exchange for stock or asset transfers within the expanded group have the same effect on the group as a dividend (i.e. they remove cash from the U.S. member(s) of the group without producing any real change in the composition of the group as a whole).

Recharge Exception for Equity Compensation

The final regulations did contain some good news for foreign based multinationals. There were numerous exceptions introduced in the final regulations that were not included when the proposed regulations were issued in April. The recharge exception for stock compensation is a good example of this and may present an opportunity for a foreign parent company to introduce debt into the U.S. group in a cashless transaction.

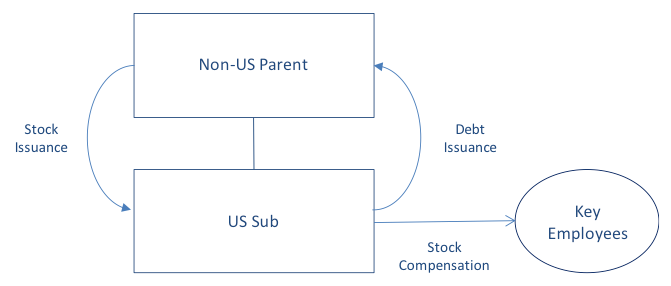

Equity compensation awards are common in the business world. For a foreign based multinational, the equity compensation to employees of its U.S. subsidiaries would come in the form of shares of the foreign parent company. There is no requirement under U.S. tax law for the foreign parent company to charge the U.S. subsidiary for the parent company shares; and often there is no charge. Below is an illustration of how these awards may be structured in a manner that pushes debt into a foreign parent’s U.S. group in a cashless transaction:

In the above example, the foreign parent company’s stock is used by its U.S. subsidiary to compensate its employees (typically key employees). Under the final regulations, it is possible for the U.S. subsidiary to issue debt to the foreign parent in an amount equal to the fair market value of the stock that it used to compensate the U.S. subsidiary’s employees. This transaction allows the U.S. subsidiary to issue debt in a cashless transaction.

This possibility may also make it desirable to increase the proportion of the compensation of U.S. employees that is in the form of stock-based compensation. That would permit additional debt to be issued by the U.S. subsidiary. Employees who would prefer more cash may be given the right to sell their foreign parent shares back to either the U.S. sub or the foreign parent.

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand Says:

If we can give one piece of advice to non-U.S. based multinationals with regard to dealing with the final regulations, it is to be proactive. Be proactive in setting up your capital structure when you establish a new U.S. subsidiary. Be proactive when a U.S. subsidiary plans on paying dividends to its foreign parent, if any U.S. group members have related-party debt to foreign group members. Be proactive in identifying and addressing potential issues under the final regulations when performing intercompany transactions involving a U.S. subsidiary if any U.S. group members have issued related-party debt. And become familiar with the various exceptions to the tainted transaction and funding rule of the final regulations. Unfortunately, unless the regulations are withdrawn by the upcoming Trump Administration, many non-U.S. based multinationals are going to be caught in them. But a prepared tax department may be able to mitigate some of the issues that arise for their company.

Disclaimer