To Carry Back, or Not to Carry Back, That is the Question

In an effort to provide liquidity to taxpayers, as part of the CARES Act, Congress has enabled taxpayers to carry back a net operating loss (NOL) arising in a taxable year beginning after December 31, 2017, and before January 1, 2021 for five taxable years, and made other changes to the Internal Revenue Code which may allow taxpayers to increase their NOLs for those years. However, there is no cookie-cutter answer to the question whether taxpayers should take advantage of some of these law changes, including the ability to carry back NOLs. In this alert, we discuss:

- The rules governing NOLs prior to TCJA and the related changes that TCJA made,

- The NOL provisions within the CARES Act,

- What a taxpayer should consider in determining whether to carry back its NOLs, and

- If it chooses to carry back its NOLs, the mechanics and anticipated timing of a refund.

NOL Provisions Pre-TCJA and the Related TCJA Changes

Prior to the passage of the TCJA, taxpayers were required to compute a regular tax NOL applying regular Code rules and an Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) NOL applying the AMT rules. Both the regular tax NOL and the AMT NOL could be carried back two years and carried forward 20 years. A taxpayer was able to offset all of its regular taxable income in a given year with a net operating loss deduction. However, generally only 90% of the taxpayer’s alternative minimum taxable income (AMTI) could be offset by the AMT NOL.

The TCJA made the following notable changes to the rules governing NOLs generated after December 31, 2017:

- Taxpayers are generally no longer able to carry back their NOLs.

- The carryforward period for NOLs is indefinite.

- A taxpayer is able to offset only 80% of its taxable income in a given year with NOL deductions.

In an apparent oversight, the carryback provision was made effective for taxable years ending after December 31, 2017, while the 80% limitation was made effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017.

Additionally, the TCJA made two notable changes with respect to the application of the AMT to corporations:

- Corporations are no longer required to pay AMT.

- The credit for AMT previously paid (minimum tax credit or MTC) was made refundable over a four-year period from 2018 through 2021.

Summary of CARES Act NOL Provisions

With respect to NOLs, the CARES Act made two substantial changes for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017, and before January 1, 2021:

- Any NOL deduction taken in those years is not subject to the 80% taxable income limitation discussed above, and

- Taxpayers can carry back NOLs arising in those taxable years for five taxable years (although they can forgo the entire carryback period).

The CARES Act also provides that an NOL carryback cannot be used to offset the Section 965(a) toll charge, and the taxpayer can choose to exclude the year or years in which it reported the Section 965(a) toll charge from the carryback period, without having to forgo the carryback altogether. However, excluding those years does not extend the carryback period.

Additionally, the CARES Act included a technical correction to the effective date of the TCJA provisions, so that an NOL that was generated in a fiscal year that began before December 31, 2017 and ended after December 31, 2017 can be carried back two years under pre-TCJA rules.

Should NOLs be carried back?

The benefit of being able to carry back NOLs is threefold:

- Taxpayers can receive cash refunds quickly, compared to carrying an NOL forward to a taxable year that has not yet closed.

- If a corporation carries an NOL back to a pre-TCJA year, the NOL can be used to offset taxable income that is subject to a 35% tax rate, rather than the 21% tax rate applicable after 2017; and

- The carryback of the NOL is permitted to offset 100% of taxable income in the carryback year, rather than only 80% of taxable income in taxable years beginning after December 31, 2020.

While a reduction in taxable income and “faster” cash refunds are typically favorable, there are several factors that a taxpayer should consider in determining whether it should carry back its NOL.

Is the Company Contractually Permitted to Carry Back the NOL and if so, Who Is Entitled to the Refund?

The first factor that should be considered is whether the company is subject to any contractual restrictions on its ability to carry back an NOL. If the company has been involved in an M&A transaction during the five-year carryback period, then it is imperative that the transaction documents are reviewed to ensure that the company is not contractually prohibited from carrying back the NOL to the pre-acquisition period.

It would seem logical that the company that generated the NOL that is being carried back should be entitled to the refund. However, that may not be the case. Even if the transaction documents permit the carryback, they may provide that the former owners are entitled to all or part of the resulting refund. In such a case, it may be possible that some sharing of the refund can be negotiated with the former owners. If the agreement is silent on the subject, there may be applicable commercial or corporate law that must be consulted to determine entitlement to the refund.

Additionally, even if the agreement is silent, certain consolidated return rules may shift the refund to the former owners. Specifically, Treasury Regulation §1.1502-21(b)(2) provides that a consolidated net operating loss (CNOL) attributable to a member of the group that can be carried back to a separate return year of that member must be carried back to the separate return year and not to any consolidated return year of the group. As a result, if the member was a member of another consolidated group prior to its acquisition, then the NOL carryback would be reported by the member’s former consolidated group and that group (rather than the member’s current consolidated group) would receive the refund. The consolidated return regulations provide limited relief from this provision by allowing a member to relinquish its carryback period to the extent it was a member of another consolidated group. However, this election (under Treasury Regulation §1.1502-21(b)(3)(ii)(B)) must be filed with the original tax return of the new consolidated group in the year in which the corporation became a member. Because the TCJA repealed the carryback provision, it is highly likely that consolidated groups did not make this election for subsidiaries acquired after 2017.

Example: On December 31, 2017, P acquired all of T’s outstanding stock from X, the common parent of the X consolidated group. T had been a member of the X group since at least 2013. On P group’s originally filed tax return for 2018, P did not make the §1.1502-21(b)(3)(ii)(B) election. In 2019, the P group incurs a CNOL of $900x, of which $300x is properly attributable to T. If the P group does not waive the carry back of its 2019 NOL in its entirety, then P group’s 2019 CNOL will be carried back to 2014, and the $300x apportioned to T generally will be carried back to the X group’s 2014 tax year (and if not absorbed, to the X group’s 2015, 2016, and 2017 tax years).

If the carryback to X group generates a refund, X will receive the refund, even though the loss that generated the refund was incurred by T while it was a member of the P group.

With that said, there is a possibility that Treasury and the IRS may issue guidance to address the consolidated return issue, as similar guidance has previously been issued. See Treasury Regulation §1.1502-21T.

The possibility of either of these issues arising is heightened due to the pre-Coronavirus environment in which M&A activity was at an all-time high.

What is the Impact of the Carryback on Previously Claimed Items?

The second factor relevant to the decision whether to carry back an NOL is the impact the carryback may have on previously claimed items (i.e., credits and deductions) that are calculated based on a company’s taxable income. In certain circumstances, a carryback may result in unfavorable treatment.

For example, non-refundable credits are available in a particular year only to the extent of the taxpayer’s tax liability without regard to the credits. One such credit is the foreign tax credit, which is generally limited to the amount of the taxpayer’s US pre-credit tax liability multiplied by its ratio of foreign sourced income in the relevant basket to its total taxable income. In many cases, a reduction in taxable income due to an NOL carryback would be applied in whole or in part to foreign source income, reducing the percentage of foreign sourced income, as well as the taxpayer’s pre-credit tax liability. While it is true that any unused creditable foreign taxes can be carried back one year or forward for up to ten years, the use of these foreign taxes to offset US tax is dependent on there being excess limitation in some year within the carryback/carry forward period. The likelihood of this is reduced due to the reduction in tax rate beginning in 2018, as well as other changes made by the TCJA to the foreign tax credit rules. Those changes are outside the scope of the alert.

Another example of an item that can be adversely affected by a carryback is the Section 250 deduction, which was added by the TCJA (a discussion of the proposed regulations promulgated under Section 250 can be found HERE). The TCJA introduced the foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) and global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) regimes to US taxpayers as the carrot and stick approach to worldwide taxation. US corporations are afforded a Section 250 deduction equal to the sum of 37.5% of their FDII and 50% of the sum of their GILTI and the related Section 78 amount. However if in any given tax year the sum of a US corporation’s FDII and GILTI exceeds its taxable income (determined with regard to NOL deductions but without regard to the Section 250 deduction), the amounts of FDII and GILTI taken into account to determine the Section 250 deduction are reduced proportionately to eliminate the excess. Unlike excess foreign tax credits, which can be carried back or forward, the Section 250 deduction is calculated annually without a carryback or carryforward provision. Therefore, if an NOL reduces taxable income to an amount that is less than the sum of FDII and GILTI, there will be a permanent reduction in the cash tax benefit of the excess NOL by 37.5% to 50%.

Wait … Where’s My Refund?

In determining the amount of the refund that will be generated by an NOL carryback, there are two additional factors that should be considered: the application of the AMT and the potential that the refund either be disallowed or applied to another tax liability.

Application of the AMT

Although corporations are no longer subject to AMT due to TCJA, all taxpayers were subject to AMT during the taxable years pre-TCJA. As a result, a taxpayer has to take into account the application of the AMT in determining the amount of its refund. In general, the AMT rules provided that a taxpayer could offset only up to 90% of its alternative minimum taxable income (AMTI) with an AMT NOL deduction and the amount of the AMT NOL had to be calculated under the AMT rules. As a result, a taxpayer that eliminates its regular tax liability with an NOL carryback may still owe AMT for the carryback year, which would reduce the available refund. Because there is currently no guidance to the contrary, it appears that taxpayers must calculate the amount of the AMT NOL that was generated in the year of the carryback. To the extent that the taxpayer has to pay AMT (which is calculated as the excess of the taxpayer’s tentative minimum tax (TMT) over its regular tax), a credit arises that can be claimed in a subsequent taxable year. In general, the amount allowable as a credit in a particular year is equal to the lesser of: (1) the AMT paid for all prior taxable years beginning after 1986 minus the amount of credit previous taken and (2) the regular tax liability of the taxpayer reduced by some credits minus the taxpayer’s TMT. For corporations, the credit became refundable beginning in 2018 as a result of TCJA and the CARES Act. However, the credit must be claimed in the first taxable year it is available, which can impact the manner of claiming the credit and the IRS’ timing to process the refund.

Reduction in the Amount of the Refund

Even after determining the amount of the refund taking into account AMT, the amount of the refund can be further reduced by adjustments that the IRS makes with respect to the taxable year to which the NOL is being carried. Under Section 6501(a), the statute of limitations on the assessment of federal income taxes generally expires three years from the due date of the return or the date on which it was filed, whichever is later. However, if an NOL carryback creates a refund for a prior taxable year, the statute of limitations for that prior year is extended to include the limitations period for the year the NOL was generated to the extent of the refund. As a result, the IRS may audit a previously closed taxable year to reduce the amount of the refund, nullifying the tax benefit of the NOL carryback. Therefore, if the taxpayer has exposure in closed years, then it should determine whether it is worth the risk of carrying back the NOL to such years as the IRS could reduce the amount of the refund.

Additionally, Section 6402 permits any tax refund to be applied against any income tax liability prior to issuing a refund. As part of TCJA, Section 965 imposed what is known as the “repatriation toll tax.” The repatriation toll tax required taxpayers to pay a one-time tax on previously untaxed earnings of specified foreign corporations, which could have been paid in installments pursuant to Section 965(h) over an eight-year period for most companies. However, for companies that had overpaid their 2017 federal income taxes, the entire overpayment was applied against the outstanding Section 965 tax liability, thus eliminating refunds or the ability to credit the overpayment to quarterly estimated taxes. Therefore, it is possible that a company’s refund could be used to offset its Section 965(h) liability rather than issued in cash. While this possibility may seem far-fetched, language to prevent this result was initially included in a draft of the Senate bill for the CARES Act, but that language was not included in the final legislation. With that said, Treasury and the IRS may issue similar guidance, because using the refund to satisfy the Section 965(h) liability seems inconsistent with the CARES Act prohibition on using the NOL carryback to offset the Section 965(a) inclusion.

Procedure to Carry Back an NOL

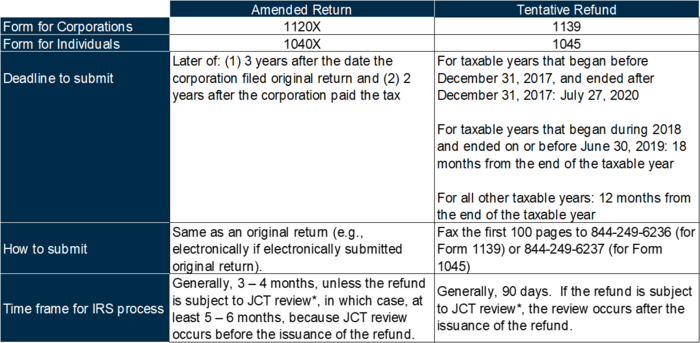

If a taxpayer chooses to carry back its NOL, it can do so by filing either an amended return or an application for a tentative refund. The following table summarizes the two approaches:

* A refund is generally subject to JCT review if the amount of the refund is in excess of $5 million, in the case of a corporation, or $2 million, for all other taxpayers.

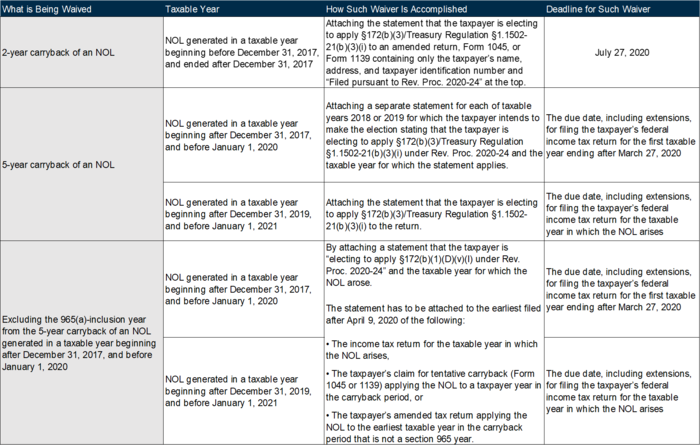

Procedure to Waive a Carryback of an NOL

Alternatively, if a taxpayer chooses to irrevocably waive the carryback of its NOL, it is important to understand how this is done and the associated deadlines.

A&M Taxand Says

At first blush, the ability to carry back an NOL is very enticing based on the prospect of a refund. However, for many taxpayers, this will not be an easy decision to make because of the complex interactions among the tax rules governing NOLs and their impact on tax benefits allowed under other Code provisions. Like most tax elections, the CARES Act rules may require sophisticated modeling in order for a taxpayer to make an informed choice.

Once the decision of whether to carry back an NOL is made, the taxpayer must still navigate a procedural minefield to ensure that the appropriate forms are filed, and a refund is issued in the timeliest manner. Both the rules governing the waiver of a carryback and the carryback and associated rules for obtaining refunds continue to be in flux.

A&M is ready to help every step of the way, click here to contact us.