Executive Compensation in the Energy Sector is Seriously Suffering. What's the Relief?

2016-Issue 3 – Over the last year, the energy sector has been plagued with low commodity prices. The plunge in crude oil and natural gas prices has in many cases shaved over 50 percent off stock prices of many exploration and production (E&P) companies. In a market where executive compensation has traditionally been tied to equity prices or total shareholder return, company boards and compensation committees are facing a quandary. With equity prices so depressed, long-term incentive awards have lost much, if not all, of their value. Restricted share awards, initially granted based on a value that compensation committees believed would support competitive compensation packages for their executives, are worth significantly less. Stock options, in many cases, are now so far “underwater” that they have become virtually worthless.

In this edition of Tax Advisor Weekly, we discuss alternative approaches to incentivize the executive team in market conditions where more traditional incentives are not effective. We also consider how to approach executive compensation in the event that circumstances ultimately dictate a balance sheet restructuring or bankruptcy filing.

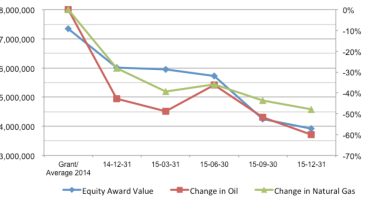

The following chart illustrates the decline in the average value of restricted stock and performance share awards made to the CEOs of the top 20 E&P companies in 2014, relative to the fall of crude oil and natural gas prices.

The chart reflects that the decline in the value of equity-based awards roughly tracks the decline in commodities prices on a percentage basis. This raises a question: How will companies structure annual and long-term incentives so that the executive compensation programs will remain competitive for retaining executive talent?

Alternative Remedies

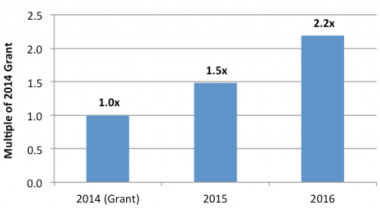

One alternative for dealing with depressed share prices would be to simply increase the number of shares granted in order to deliver the same competitive market compensation to the executives. There are several problems with this approach, including the additional dilution that other shareholders would be absorbing, whether enough shares would be available under the incentive plans (since this approach would greatly increase the “burn rate” of shares available for issuance under such plans) and the “upside risk”— that a sudden bounce in share prices could result in an unintended windfall for the executives. The following chart reflects the change in the number of shares that would need to be granted to executives to achieve the same aggregate award value received in 2014, based on the decline in E&P company share prices, for 2015 and 2016.

These issues, among others, make this solution undesirable to company boards and investors alike. Based on these and other concerns, simply awarding additional equity has its challenges.

In this atmosphere, how do companies keep and motivate key executives? How can companies measure performance in a manner that is not enslaved to commodities prices? To address these concerns, many E&P companies are considering:

- Reducing the participation in equity awards;

- Converting long-term incentive arrangements from equity-based awards to cash incentive programs;

- Modifying annual performance metrics to be more focused on cost-cutting;

- Implementing retention programs focused on key employees and executives; and/or

- Modifying performance metrics to factor out the impact of falling commodities prices.

Note that there is no “one size fits all” prescription that will be effective in every case. Rather, each company’s condition must be individually examined to determine the best treatment.

Balance Sheet Restructuring on the Horizon?

If a balance sheet restructuring or bankruptcy filing is on the horizon, certain immediate changes to the incentive plans should be considered in order to motivate and retain key talent. Because debtors’ equity will generally become worthless in the event of a bankruptcy filing, a common defensive approach is to collapse the annual and long-term incentive program into a single cash-based incentive program that pays out over shorter measurement periods based on hitting established performance metrics. In addition, often the annual incentive program will be modified to incorporate performance metrics that are more commonly utilized in bankruptcy and acceptable to the creditors. This allows the annual incentive plan to be easily transitioned into a key employee incentive plan (KEIP) in the event of a filing, thus reducing disruption to the executive ranks.

Heading to the ER – Bankruptcy Filing

In the event of a bankruptcy filing, the type and magnitude of the changes to the compensation plans will be influenced by the anticipated time frame to perform a restructuring or emergence from bankruptcy. In a “free fall” situation (where the debtor enters into bankruptcy proceedings in response to a significant liquidity event without having restructuring arrangements in place with its major stakeholders), the entire incentive compensation program will generally need to be revamped. In a prepackaged bankruptcy (where the debtor has negotiated, documented and disclosed to creditors a plan of reorganization that has been approved by creditors before the bankruptcy case is filed), there might be fewer changes to existing incentive programs and more of an emphasis on equity to be granted to management upon emergence from bankruptcy. Many bankruptcy filings will fall somewhere in between these two extremes, but in any case, the annual and long-term incentive programs will need to be adjusted or overhauled.

During bankruptcy, the common treatment of the annual and long-term incentive plans is illustrated in the following table:

|

Impact of Bankruptcy on Incentive Plans |

|

|

Annual Incentives |

|

|

Long-Term Incentives |

|

KEIP-ing Executives Engaged in the Recovery Process

Companies under financial stress want to retain key executives because their substantial industry experience and company-specific knowledge are necessary to continue the operation of the company’s business and to support the company’s turnaround. On the other hand, such executives may be reluctant to remain with the company during distressed periods in the midst of job instability and where annual bonuses, long-term incentives and other compensation may no longer offer attractive payouts or value.

To address these conflicting interests, prior to 2005, companies entering into bankruptcy typically retained executives by implementing key employee retention plans (KERPs) whereby executives were paid for simply remaining on the job through specified dates. However, changes to the bankruptcy code enacted in 2005 effectively ended the use of KERPs for “insiders.” As a result, many companies today implement KEIPs, which are performance-based plans that are essentially designed to fall outside the bankruptcy code restrictions on the use of KERPs, for the insiders. Conversely, retention plans are generally used for “non-insiders.”

Accordingly, one of the first items to understand is whether the plan’s participants are insiders. To the extent a bankruptcy court determines that plan participants are not insiders, the plan will not be subject to the bankruptcy code restrictions on the use of a KERP. The bankruptcy code defines insider as a director, an officer, a person in control or a general partner of the debtor, or a relative thereof, as well as a partnership in which the debtor is a general partner. However, the list is not exhaustive and the terms “director” and “officer” are not specifically defined in the statute. Therefore, a determination of which employees are insiders must be made.

KEIP Considerations for E&P Companies

Companies should consider various factors when implementing a KEIP. To avoid classification as a KERP, a KEIP covering insider participants should incentivize such persons to perform well and not simply induce them to remain employed. Consequently, KEIPs should be structured to pay out based upon the achievement of performance metrics and goals determined by the company. Common performance metrics generally used by E&P companies in bankruptcy include:

- Production targets;

- Expense reductions (lease operating or general & administrative expenses);

- Financial metrics (EBITDA, EBITDAR);

- Confirmation of plan of reorganization/emergence from bankruptcy by a specified date; and/or

- Amount of proceeds realized from sale of company or designated assets.

The performance metrics, however, must be carefully chosen and structured to be sufficiently challenging, based on the circumstances of the particular company. The metrics should also coincide with the company’s business plan or objectives. Bankruptcy courts have refused to approve KEIPs where performance metrics are easily attainable and considered “lay-ups,” finding such arrangements to be impermissible retention plans.

Companies should give careful consideration to the timing of payments and the length of the performance periods. Quarterly performance periods are common, as annual plans usually could be perceived as too long of a performance period in uncertain financial times. The amount of potential payout is also a consideration, as it should be sufficiently motivating, but should be reasonable when compared to other similar payments made in bankruptcy. The potential payout should also result in total compensation that is reasonable when compared to market compensation levels.

In addition to the company’s board of directors approving the arrangement, there will be several other parties that will weigh in on the design and payout amounts of the KEIP. Creditors’ input should be anticipated, since there will be a focus on cash flow / profit, and the company should expect negotiations in this regard. It is less of a challenge to get a KEIP approved in bankruptcy court if it is supported by the creditors.

Not surprisingly, bankruptcy courts have generally disapproved of KEIPs where the majority of the work required to earn the payments is performed prior to the court hearing date. However, some courts have approved KEIPs despite the fact that the sale of a company’s most valuable assets had already been approved and therefore a majority of the KEIP performance metric had been achieved by the time the motion for KEIP approval reached the court. In one case, while acknowledging concerns about the timing of the motion for KEIP approval, the court gave substantial deference to the fact that the debtors had provided the creditors’ committee with the opportunity to consider the KEIP and that the committee ultimately supported the plan. These cases highlight the importance of providing creditors’ committees an opportunity to consider a KEIP and, if possible, obtaining the committee’s support when seeking the court’s approval of the plan.

Finally, there will usually be negotiations with the U.S. Trustee relating to the KEIP. These discussions are generally around the performance metrics utilized and the amount of the potential payments.

Timing of Implementation

Generally, it is recommended that an incentive plan with KEIP-like features be implemented as soon as possible when conditions warrant, incentivizing executives and deterring attrition. Implementing such plans prior to entering bankruptcy is much more efficient, and instituting a KEIP during bankruptcy is often a lengthy and contested process, and many employees may leave due to uncertainty before the plan is finalized. Furthermore, implementing the framework of a KEIP before a bankruptcy proceeding is contemplated may lead to fewer distractions for key employees, allowing them to focus on aiding the company’s overall turnaround effort to maximize the estate. If an appropriate plan is implemented prior to a bankruptcy filing, it may be accepted by the bankruptcy court, although further adjustments may be needed after discussions with all interested parties.

Post-Emergence Incentive and Retention

Unfortunately, the battle to retain and motivate key employees does not end simply upon exit from bankruptcy. When emerging from bankruptcy, most pre-bankruptcy company stock and unvested equity awards held by employees have lost their value. Lack of meaningful equity ownership in the go-forward entity, coupled with an uncertain company future, leads to difficulties retaining and motivating key executives post-emergence. Consequently, emergence equity grants are a way to ensure that companies retain motivated personnel who are vital to a successful post-emergence entity.

Some important considerations for emergence grants include:

- What percentage of the new company’s equity should be reserved for employee equity awards?

- What portion of the equity pool should actually be granted at emergence?

- Who should receive emergence grants (officers, middle management, all employees)?

- How will the emergence grants be structured (i.e., size and type of award, vesting, etc.)?

Most companies emerging from bankruptcy reserve a portion of the new company’s shares in order to provide equity compensation to employees. The typical share reserve depends on the size of the company, with smaller companies tending to have a larger percentage of shares set aside than larger companies. Equity grants are typically made in the form of stock options and/or restricted stock and, to a lesser degree, performance shares. Depending on the company’s needs post-emergence, the awards can be structured as a retention vehicle (vesting based on time), an incentive vehicle (vesting based on performance) or a combination of the two.

As the creditors will generally become a significant shareholder, companies work closely with the creditors' committee in determining which executives are key post-emergence and, accordingly, who should be granted post-emergence grants. The discussion of the post-emergence grants generally comes up as part of the confirmation plan.

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand Says:

Companies in an unhealthy financial condition, whether or not a bankruptcy filing is anticipated, are especially challenged with retaining and motivating key employees. Incentive programs, when properly structured, can help bridge the compensation gap between the onset of financial ills and a healthy go-forward restructuring. If implementing a KEIP, it is vital to structure the plan so that it properly incentivizes participants to achieve the desired results. Additionally, time is of the essence — as a company draws closer to emerging from bankruptcy, it becomes increasingly more difficult to get the all-important buy-in from the creditors' committee, other key constituents and, ultimately, the court. Accordingly, it is most advantageous to develop an incentive plan with KEIP-like features during the pre-filing period. As the saying goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Just as incentive plans may be effective tools prior to and during the bankruptcy process, equity granted by companies upon emergence from bankruptcy is useful in motivating and retaining employees after the bankruptcy process has concluded. Key considerations include the size of the post-emergence equity pool, the amount of equity to grant at emergence, the determination of who will receive emergence grants and the structure of awards.

When a company’s financial health is not optimal, a general practitioner may not have the required expertise to guide the company through these issues during the recovery period, so retaining a qualified compensation specialist is critical.

For More Information

JD Ivy

Managing Director, Dallas

+1 214 438 1028

Rob Casburn

Senior Director, Dallas

+1 214 438 8470

James Deets

Senior Director, Dallas

Mindy Davidson

Senior Director, Houston

+1 713 547 3711

Allison Hoeinghaus

Senior Director, Dallas

+1 214 438 1037

Disclaimer

are subject to change. Readers are reminded that they should not consider this publication to be a recommendation to undertake any tax position, nor consider the information contained herein to be complete. Before any item or treatment is reported or excluded from reporting on tax returns, financial statements or any other document, for any reason, readers should thoroughly evaluate their specific facts and circumstances, and obtain the advice and assistance of qualified tax advisers. The information reported in this publication may not continue to apply to a reader's situation as a result of changing laws and associated authoritative literature, and readers are reminded to consult with their tax or other professional advisers before determining if any information contained herein remains applicable to their facts and circumstances.

About Alvarez & Marsal Taxand

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand, an affiliate of Alvarez & Marsal (A&M), a leading global professional services firm, is an independent tax group made up of experienced tax professionals dedicated to providing customized tax advice to clients and investors across a broad range of industries. Its professionals extend A&M's commitment to offering clients a choice in advisers who are free from audit-based conflicts of interest and bring an unyielding commitment to delivering responsive client service. A&M Taxand has offices in major metropolitan markets throughout the United States and serves the United Kingdom from its base in London.

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand is a founder of Taxand, the world's largest independent tax organization, which provides high quality, integrated tax advice worldwide. Taxand professionals, including almost 400 partners and more than 2,000 advisers in nearly 50 countries, grasp both the fine points of tax and the broader strategic implications, helping you mitigate risk, manage your tax burden and drive the performance of your business.

To learn more, visit www.alvarezandmarsal.com or www.taxand.com