The Partnership Retirement Plan Time Bomb (Part 1)

This article was first published on www.legalbusinessinsider.com.

This is the first installment of a three-part series dealing with law firm retirement plan obligations.

Case Study:

George is the managing partner of a 100 partner multi-office United States law firm. He and the firm’s Chief Financial Officer have been watching the firm’s liability for partners’ retirement benefits keep growing. Partners have retired and new partners have been admitted to the firm to replace them. All of these partners have been accruing retirement benefits that the firm someday will have to pay. Although George and the CFO really don’t have a reliable handle on the size of the probable liability, they know it is large – and growing. And they both wonder how it will be paid. New partners are concerned about taking on this debt, and current partners hope someone will be there to pay them when they retire.

About ten years ago George’s firm voted to adopt a nonqualified plan that would pay each retired partner $250,000 a year for fifteen years. George’s firm helped many clients implement nonqualified retirement plans for senior executives. The partners saw first-hand the popularity of these plans and how they helped executives build a financial base for retirement.

After much discussion, the partners also concluded that a nonqualified retirement plan would help retain their best talent and assist in attracting star performers to the firm. While these discussions were going on, the firm’s per-partner earnings were steadily increasing and the partners concluded that this was a plan they could afford. All active partners were covered, including partners close to retirement. Although since then the average partner’s earnings has increased each year, the retirement payment has not changed. Partners have been encouraged to save, but firm approved qualified savings plans will not provide sufficient income in retirement.

The partners saw the retirement plan as a way to help finance their own retirement and a way to bind partners closer to the firm. Having a retirement plan also made the firm more competitive in recruiting lateral partners, who gave much weight to financial inducements. Of course there is no third party “employer” to pay these benefits. The only source of benefit payments is the partners themselves. The partners understood this, but little attention was paid to exactly how this in practice would work. The general thinking was “I will pay the benefits for partners who retired before me, and in turn my successors will pay for my benefits”.

Another unwelcome fact emerged when the CFO recently began digging into this issue. Most analyses of retirement plan liabilities focus on the present value of the liability, which is a balance sheet approach. The real issue for a law firm is the actual amount of cash that will be required to meet the firm’s obligation, and when that cash will be needed. George, who participates in the retirement program, wonders how the firm will deal with this significant cash flow commitment.

We have been working with several law firms which have been struggling to deal with this issue. In this environment, the firms’ managing partners are facing the prospect of ballooning liabilities for partner retirement payments. Although there had been general agreement that these plans should be adopted, little thought was given to the eventual magnitude of the liability, or how the firms would come up with the cash to meet these retirement payments when they came due.

Times have changed

The relationship of partners and their firms has changed dramatically in recent years. In the past, lawyers joined firms soon after graduating from law school and intended to stay there until retirement. Assuming they were admitted to partnership, a lawyer could spend his or her entire working life at a single firm.

In this environment, active partners acknowledged the obligation to pay for retired partners. Retirees were those who had come before and had helped build the firm to where it is now. Active partners accepted this financial responsibility, confident that when it was their turn to retire, their right to retirement payments would be met by the firm.

The bond of mutual loyalties has somewhat frayed, with lawyers often changing firms to better their career and compensation prospects, and firms making staffing changes as the economy rises and falls. Lateral partners typically do not feel the same obligation to support already retired partners, and have to wonder whether yet-to-be-admitted partners will want to support them in retirement. Who then will be motivated to meet the firm’s obligation to retired partners?

Firm mergers have sometimes brought with them a liability for partner retirement payments. Partners in the surviving firm may be paying benefits to partners they never knew. The magnitude of this inherited liability often is not adequately analyzed until after the merger is consummated.

Also, the ratio of staff to partners in many firms has gone down, with fewer staff persons working to support each active partner. This makes it even harder to pay retired partners.

Who then will be motivated to meet the firm’s obligation to retired partners?

The origin of the retirement obligation

Payments to retired partners serve many purposes, including:

- Payments to founding partners as “purchase price” for the firm they created

- Payment for uncollected receivables or work-in-progress

- Payment for goodwill

- An inducement to retire when there was no legal obligation to leave

- As a supplement to the retiring partner’s other retirement income

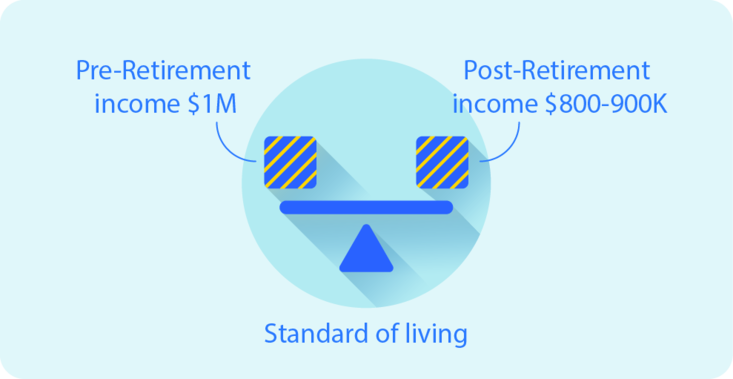

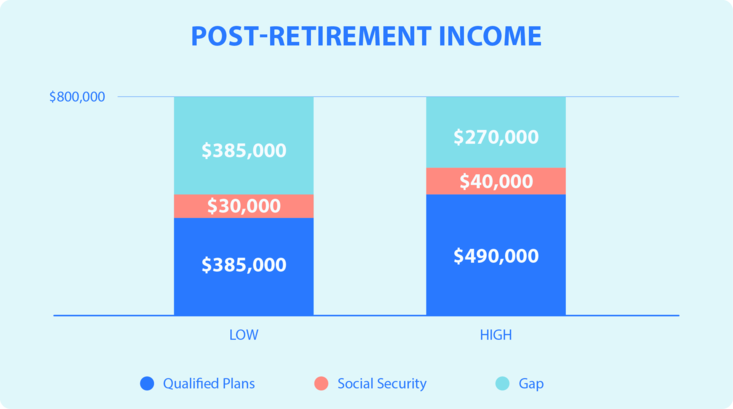

A commonly accepted guideline states that in retirement a high-earning individual will need about 80-90% of his or her pre-retirement income in order to maintain his or her pre-retirement standard of living. In other words, a partner earning $1,000,000 a year immediately prior to retirement will need $800,000 to $900,000 a year following retirement, and this amount will remain steady (barring inflation) for the remainder of his or her life.

Of course the retiree can expect to receive other income:

Social security

Most partners can expect to receive $30,000 to $40,000 a year

Qualified retirement plans

Assuming the firm maintains both a defined benefit (DB) plan and a defined contribution (DC) plan, because of qualified plan statutory limitations the maximum combined benefit that reasonably can be expected is an annual retirement benefit of from $385,000 to $490,000.

Assuming a mid-point of $475,000, the partner would need at least an additional $325,000 or so a year in retirement income to meet the 80% threshold. Some of the shortfall might be made up from personally accumulated assets, or if the partner continues working, but at some point that probably will end.

Many firms will seek to have the shortfall made up, at least in part, by implementing a nonqualified retirement plan for partners. Such a plan can be tailored to meet the specific objectives of the firm and can be adopted on a discriminatory basis, meaning that no non-partners need be included. Once adopted, of course, the nonqualified partner retirement plan becomes an obligation of the firm to its partners.

Nonqualified retirement plans are a frequent solution

The absence of qualified plan restrictions have made nonqualified retirement plans a solution many businesses have adopted. Nonqualified plans afford enormous flexibility in design and can be used to cover only selected individuals.

“Top hat” rules generally restrict nonqualified plans from covering the rank-and-file. In addition, Internal Revenue Code Section 409A has eliminated some of the almost unlimited access to accrued benefits, but most companies have figured out how to deal with these relatively new rules. Whether permitting workers to defer substantial amounts of income until a later date, or permitting employers to provide generous retirement benefits, nonqualified plans are a tried-and-true solution.

Although partners would not seem to be “employees” as that term is commonly understood, the nonqualified plans rules and Section 409A broadly apply in the partnership situation and to law firm retirement plans.

Popularity of nonqualified benefit arrangements

Nonqualified benefit arrangements satisfy a broad variety of company needs, so it is not surprising that they have been adopted by many businesses. A recent survey of larger companies found that 84% sponsor some form of nonqualified arrangement and that 71% include some type of employer paid benefit. Thus it is not hard to understand why law firms, seeing the example of their clients, look to nonqualified plans to satisfy their own requirements.

Who pays?

In most larger business situations, the executives and owners represent two different economic interests. Nonqualified plan participants look to the employer-company to satisfy plan obligations. Of course, in a law firm, partners are their own employers, so the interests of employer and workers tend to merge. However, in a retirement benefit context, the partners still look to the firm-employer to make good on the promise. This of course brings up a whole range of issues that must be faced.

The nonqualified plan trap

Nonqualified plans by their terms are not “funded”. That is, funds cannot formally be set aside (beyond the employer’s reach) to satisfy the promised benefits when they come due. Therefore, companies (and law firms) sometimes make extravagant promises without worrying about where the cash will come from to pay these benefits when they later mature.

Qualified plans must be funded, which means that cash has to be set aside in trust to pay the promised benefits. This provides at least some brake on the generosity of employers in providing benefits.

Many employers (and some law firms) do set aside funds informally designated as funding for nonqualified benefits. “Rabbi trusts” are often used and they provide some level of comfort for plan participants, but this still is short of the protections offered by qualified plan trusts.

A recent study showed that 62% of companies informally fund their nonqualified plan liabilities. Reasons for funding include improving benefit security and mitigating the profit and loss impact of the plan. Of those who do fund, 54% use COLI (company owned life insurance) aggregate funded arrangements as the funding vehicle for long-term obligations. The percentage of law firms that have funded their nonqualified plans would seem to be much lower.

For many law firm partners, the absence of funding means that their firm’s promise provides the only assurance that retirement benefits will be paid when they come due.

What to do now?

George, and other managing partners like him, are right to be concerned about their firm’s partner retirement plan liability. These benefits are firm obligations which must be paid. Even with a “cap” on retirement payments that many firms have in place, the cash outlay is significant. And, if a firm hits the cap and limits its retirement payouts, it means that the full amount of expected income that retired partners were counting on will not be received.

The first step is to get a fix on the amount of the projected cash flow liability. Taking into account partner turnover and expected mortality, just how much can the firm expect to pay and when? Only then can the firm really address this issue.

Some firms have just thrown in the towel and either frozen or cancelled their plans. Even with a frozen plan, however, the already accrued retirement plan liability may be substantial. Also, freezing a retirement plan leaves the partners to individually deal with accumulating adequate funds to support their lifestyle in retirement. This also means that the partners have walked away from the considerable leverage and economy of scale that would be available through a firm sponsored retirement program.

Even if a firm has capped the annual amount that can be paid in retirement benefits, the amount up to the cap will continue to be a significant drag on currently distributable earnings.

If the firm decides to begin allocating funds to meet this obligation, some thorny issues must be addressed:

- How much cash should be set aside annually

- How much of the total obligation should be targeted for funding

- On what basis should the funding cost be allocated

- How should the funds be invested

Recognizing that there is an issue is the first step in dealing with it. Many firms have funded a substantial part of their partner retirement benefit liability. For those that haven’t, the passage of time will not make the problem go away.

The firm’s unfunded partner retirement plan obligation has been keeping George up at night. And George isn’t the only managing partner suffering from insomnia.