Survey Design Best Practice – Behavioural Economics Offers New Clues

Predicting winters

“Winter is coming” or, as we now know more accurately, winter will make a fleeting attempt at descending but will be gamely battled away. So much for fictional prophecies and polls. In the real world, as a new wave of election campaigns have been launched - not least in the U.S. for its highest office and across Europe, both at institutional and Member State levels - so too has dawned survey season, with researchers formulating and posing a wide array of questions to eager cohorts of the electorate in the hope of collating opinion, gauging sentiment and forecasting election outcomes. But what to make of such surveys, and the predictions drawn from them? Can we hold as much store in them as around the arrival of a fictional winter?

In its most recent 2019 release, the U.K. Electoral Commission’s aptly-titled “Winter Tracker” – an annual survey tracking public sentiment towards the process of voting and democracy in the U.K. – touched on the notion of voter engagement.[1] The research found confidence in elections have fallen to 69% in 2019, from a high of 76% - the highest level since the survey began - in 2016. The Commission noted that the 2016 survey just so happened to have coincided with the referendum on the U.K.’s membership of the European Union, an event that had attracted a remarkably high voter turn-out (at 72.2%).[2]

The Commission went on to surmise that the levels of confidence in an election and voter engagement may somehow be connected.[3] Although it did not seek to explain what could lie behind such a link, the Commission’s finding may well be with merit, in underscoring a relationship between a voter’s level of emotional engagement and the level of confidence that they may subsequently go on to express within a survey setting. In short, it is entirely plausible that human emotions play a part in how individuals respond to survey questions.

Behavioural economics and survey design

Economists have long relied on surveys as powerful tools to elicit information from individuals. They have used surveys to gain valuable insights into likely consumer responses to price changes, to understand relative preferences amongst competing products and to predict future take-up of new offerings. Economic regulators have used surveys to assess business opinion on regulatory actions and to capture preferences amongst alternative regulatory proposals. Competition economists have used surveys to frame their analyses of the likely effects of anti-competitive conduct or mergers within markets under investigation.

A previous edition of A&M’s Raising the Bar explored the novel applications that behavioural economics - the branch of the field marrying psychology with economic decision-making – was being utilized for, and its role in explaining supposedly ‘irrational’ or ‘sub-optimal’ decisions made by individuals in different settings.[4] As behavioural concepts become more deeply embedded within mainstream economics and the range of their application widens, economists have started to turn behavioural insights to the field of survey design.[5] Their research is starting to provide valuable survey design tips.

Specifically, behaviourists are examining the complex relationship between the manner in which surveys are constructed and the types of responses that different types of questions may in turn generate. How questions are framed, what order they are presented in and how a survey is administered all appear to have a bearing on how respondents interpret questions and how they may choose to respond. Taken together with a respondent’s inherent biases, which will also contribute to influencing their responses, it starts to become clear that the resulting interpretive power of a survey will derive largely, if not wholly, from its precise construct.

Addressing potential biases

Consider the following example:

Q1. How likely are you to purchase this subscription, if priced at £100?

Q2. What is the most you are prepared to pay for this subscription?

A respondent may originally have been willing to pay up to £150 for the subscription but having been told in Q1 that there is a possibility that it could be priced at £100, he may reevaluate his original willingness to part with £150, reducing the figure he specifies in response to Q2. This effect is known as ‘anchoring’, with a respondent seeing £100 as an ‘anchor’ around which to gravitate. Indeed, simply changing the order of the two questions could change the result of the survey.

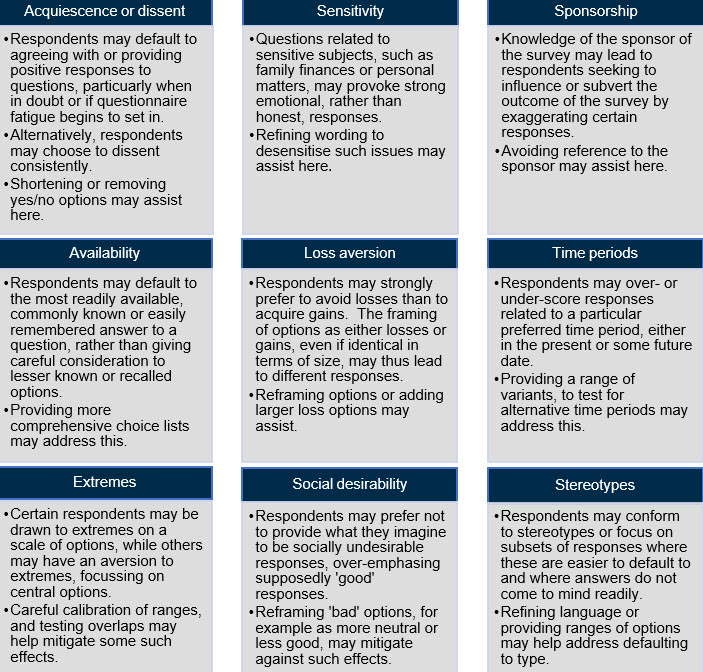

There are numerous similar effects and behavioural biases of this nature that survey architects are now analysing, in their quest to design better surveys in order to garner more reliable and meaningful results. The graphic below sets out just a few such examples.

Trust in surveys

In addition to behavioural considerations are of course still the normal practical challenges faced by survey practitioners, amongst others including: establishing the length of the survey to fit within time constraints, deciding on the mechanism to administer the survey (be it face-to-face, online or by telephone), selecting the appropriate population (or sub-sets of population) to target, securing sufficient levels of engagement and determining acceptable response rates in order to render the whole endeavour both suitably representative and sufficiently valuable. All in all, it is no wonder that executing surveys is an involved and unpredictable business, with many questioning the extent to which they may be trusted. A recent U.S. poll conducted in December 2018 found that, whilst there were patently expected differences as between the political left and right, the majority of registered voters (at 52%) were doubtful about surveys they heard about in the news media, with some 19% saying they “almost never” believed that polls were accurate.[6] Permitting behavioural economists to apply their insights to the design of polls and surveys, refining them in order to mitigate known biases as far as practicable, may go some way to restoring trust in the construct of and predictions subsequently drawn from surveys. In the meantime, winter may yet be on its way.

[1] “Winter Tracking Research 2019: Data Toplines and Key Findings; Prepared for: Electoral Commission”; BMG Research, 2019.

[2] https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/find-information-by-subject/elections-and-referendums/past-elections-and-referendums/eu-referendum/electorate-and-count-information

[3] https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/our-work/our-research/public-opinion-surveys/winter-tracker

[4] “To Nudge or Not to Nudge: Competition in Retail Financial Services”; A&M Raising the Bar, April 2014.

[5] “A synthesis of behavioural and mainstream economics”, Robert Aumann, May 2019.