Private Exchanges, Healthcare Costs and Employee Affordability

Created as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), public exchanges have enrolled more than eight million Americans. They provide an online consumer marketplace for the direct purchase of health insurance, as well as a mechanism for the payment of insurance premium subsidies for families earning less than $94,200 per year.

Private exchanges have also emerged, though at a far lower profile than its public brethren. Among the benefits touted include more predictable employer costs (i.e., reduced uncertainty), lower cost trends, expanded employee benefit choices, reduced administrative burden, increased competition and higher quality.

This article focuses on the predominant Multi-Channel Private Exchange model (MCPE). Others include the single-channel insurer (e.g., Cigna) and technology platform (e.g., hCentive). The multi-channel model is based on a defined contribution (fixed payment) made by the employer to a broker / consultant who administers the entire health benefit administration process (i.e., plan offerings, employee enrollment, decision support, regulatory compliance and administrative support).

The value proposition, though appealing, does not adequately consider the hidden impact of cost shifting and the growing unaffordability of care delivery. It also removes management from the use of healthcare benefits as a point of differentiation for employee recruitment and retention.

From a societal perspective, active employer engagement is needed to accelerate the reform of an inefficient U.S. care delivery system.

MCPE Expected to Rapidly Increase Enrollment

Private health exchanges have enrolled three million employees, accounting for 1.8% of the 168 million Americans with employer sponsored insurance.1 Some of the companies using these exchanges include Walgreens, Sears and Darden – all with a high percentage of low-wage employees.

A recent Kaiser / HRET survey of large firms (>200 employees) suggests 13% are considering offering benefits through a private exchange and 23% are considering defined contribution (i.e., a fixed payment by the employer for healthcare insurance),2 while a Health Research Institute survey suggests that 32% of employers are considering shifting their employees to a private exchange within the next three years.3

MCPE Increase the Predictability of Employer Health Expenditures

The premise of private exchanges is defined contribution. Payment can be solely determined based on operating performance requirements (i.e., profit targets) or include other factors, such as the overall rate of healthcare inflation and the importance of affordable health benefits.

In 2011, 58.5% of workers with health coverage were in self-insured plans, the majority in firms with >200 employees.4,5.Self-insured firms currently are at-risk for medical and pharmacy claims, pay for provider network and claim administration costs, and utilize stop-loss and other risk-management techniques to create corridors of potential expenditures. Defined contribution, in essence represents “Back to the Future” by allowing insurers and brokers to re-establish premiums associated with fully-insured plans. It also eliminates the ability of employers to directly manage healthcare expenditures in a period of re-accelerating healthcare costs.

MCPE Reduce the Healthcare Cost Trend for Employers

Healthcare expenditures for private businesses are forecast by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to accelerate from a 3.2% compound annual growth rate in 2009-2014 to 5.3% in 2014-19. The acceleration is being driven by an improving economy, provider consolidation, cost shifting to private employers, IT infrastructure investment pass through and PPACA taxes. Fundamental drivers of rising costs including fee-for-service reimbursement, system focus on acute intervention, limited competition (providers, insurers, suppliers, specialty drugs) and inadequate consumer (patient) engagement. Private exchanges do not address these fundamental issues.

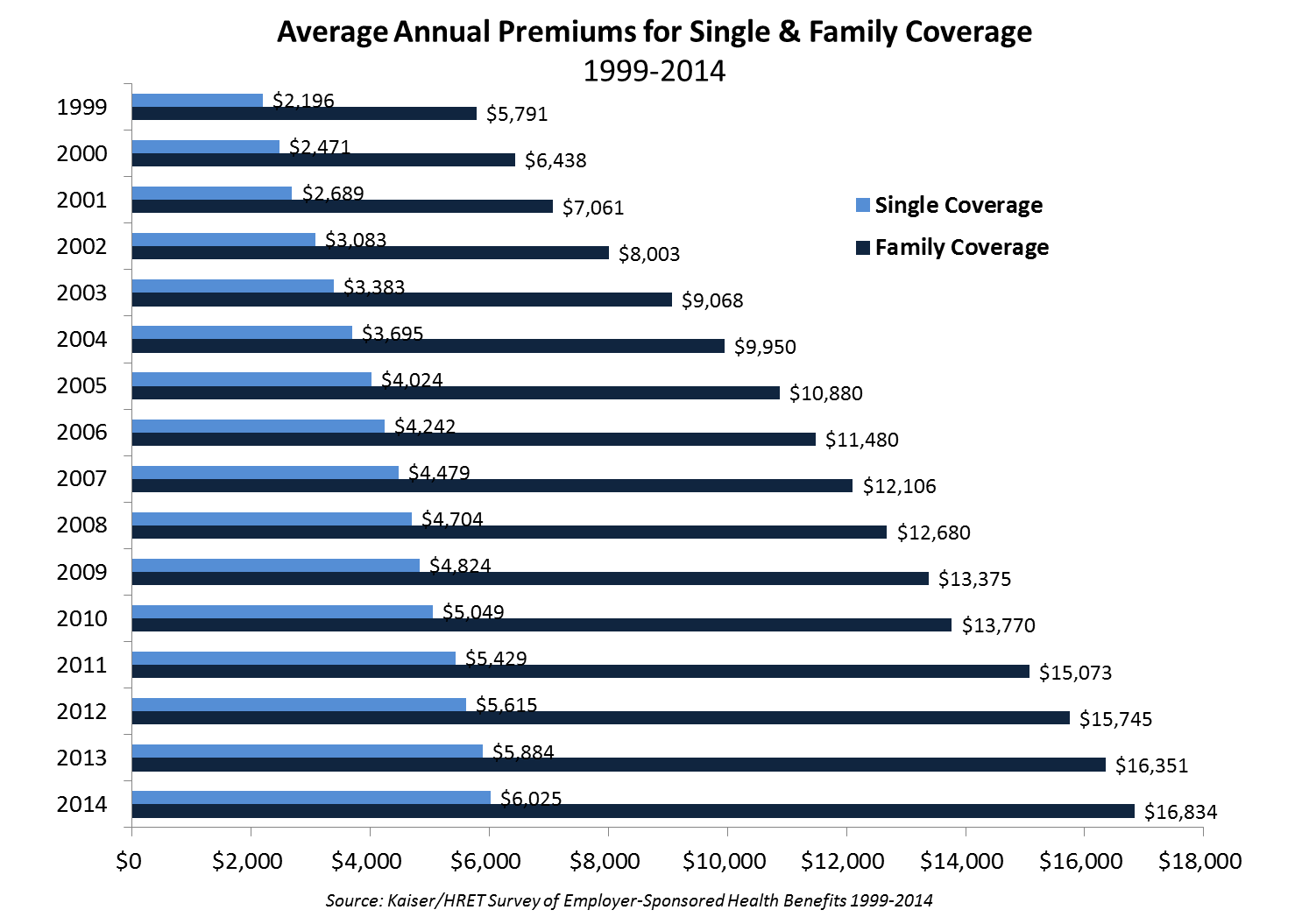

Lower costs to employers imply higher costs for employees, as evidenced by recent history. Since 1999, the growth in worker contributions to health insurance premiums (212%) have exceeded those of employers (191%), as well as their earnings growth (54%) and the inflation rate (42%).5

The average premium paid by workers for single coverage is $1,085 (18% of cost), while for family coverage it is $4,882 (29%). Workers offered health insurance at lower wage firms – 35% of employees earn <$23,000, the 25th percentile of national wages – pay more ($6,472) and a higher percent of the total cost (46%) for a lower cost plan ($14,177), than employees at high-wage firms – 35% of employees earn >$57,000, the 75th percentile of national wages5 These figures exclude rising out-of-pocket costs, estimated at $2,239 in 2013.6

Most American workers have already passed the threshold of affordability. Real household income adjusted for inflation has declined 8.1% from $56,779 in 2008 to $52,163 in 2013.7

Lower Employer Costs May Increase Absenteeism and Presenteeism

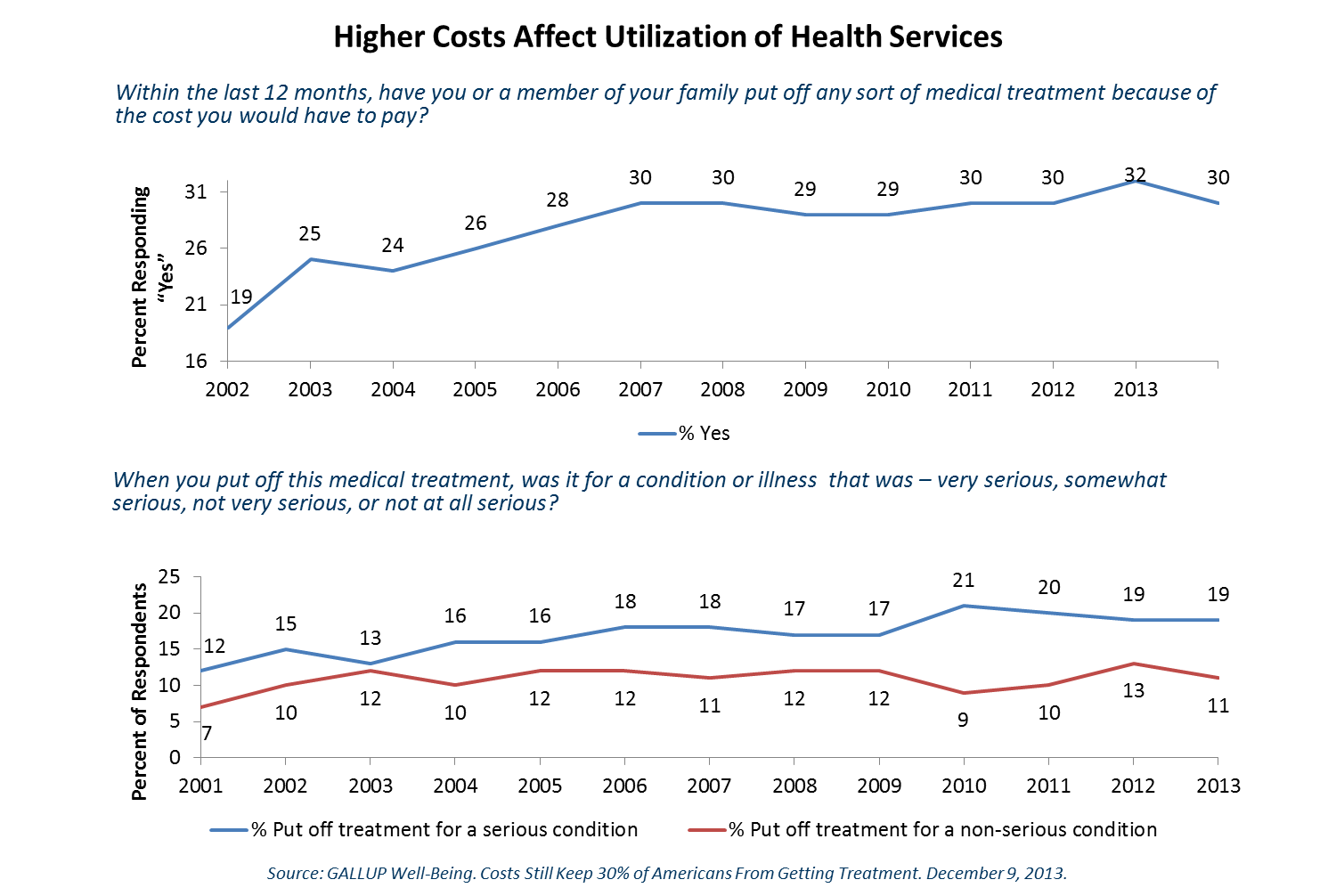

Higher out-of-pocket costs are affecting consumer behavior, including the overall utilization of health services. Approximately 30% of consumers have deferred visiting a physician, undergoing a test, filling a prescription or complying with treatment due to economic reasons. In one-third of all cases, the consumer believes treatment was delayed for a serious condition. Worse outcomes and higher costs are likely, as preventable or reversible conditions progress to more severe forms.

Indirect employee costs such as absenteeism (work loss days per person) and presenteeism (lost productivity at work) may result from illness affecting the worker or anyone within the employee’s immediate social network. Presenteeism represents a more subtle source of lost productivity, but its costs often far exceed those due to absenteeism.8 Presenteeism and absenteeism often represents “hidden” cost to employers. Longer-term, deferred or sub-optimal treatment due to healthcare affordability concerns may result in the emergence of more significant medical conditions.

MCPE Increase Employee Plan Choices, Not Market Competition

Private exchanges are likely to increase plan choice. However, the vast majority of states already have highly concentrated health insurance markets, with a Hirfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) exceeding 2500.9 The HHI is a measure of market concentration, with higher values indicating less competition. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama has a HHI of 9175 and a market share of 96%.Conversely, Oregon is moderately concentrated, having an HHI of 1606, due to its seven insurers with a market share of at least 5% and a leading competitor at 24% share.9 The median HHI within the U.S.is 3595; most markets have only two-to-four major competitors.9

Recent acquisitions by leading insurance companies of smaller commercial, Medicare Advantage and Medicaid Managed care plans have further concentrated the market. Multiple plans from the same insurer do not beget price competition.

MCPE Don’t Increase Quality (or Value)

An association between cost and quality has been incorrectly assumed to exist. In 2007, an IOM roundtable indicated no definitive relationship, based on evidence-based medicine, between regional differences in spending and the “content, quality and outcome of care.”10 A Commonwealth Fund study examined the relationship between quality and cost showed similar results.11 Lastly, according to a recent publication in the Annals of Internal Medicine, “evidence of the direction of association between healthcare quality and cost is inconsistent. Most studies have found that the association between quality and cost is small to moderate, regardless of whether the direction is positive or negative.”12

Private exchanges are not focused on value creation; i.e., the fundamental relationship between cost and quality. They are intended to reduce costs and not reform a system badly in need of change. The lack of price transparency for inpatient, outpatient and ambulatory services will continue.

MCPE Help Brokers and Benefit Consulting Firms

Healthcare benefit consultants have described private exchanges as innovative, revolutionary and transformative.13 Among consulting firms that have invested heavily in private exchanges are: Aon-Hewitt (Aon Active Health Exchange), Mercer (Mercer Marketplace), Buck Consultants (RightOpt) and Towers Watson (OneExchange). After acquiring Extended Health, a Medicare private exchange in 2012, Towers Watson acquired Liazon in November 2013 for $215 million for its OneExchange technology platform, allowing “employers to give their full- and part-time employees (as well as their retirees) access to private and public health insurance exchanges”.14

Private exchanges represent an opportunity to consolidate broker / consultant relationships with clients, while extending the range of fee or commission-based offerings. For example, the Mercer Marketplace offers “wrap around” products for accident, hospital indemnity and critical illnesses (e.g., cancer, heart) represent an incremental revenue opportunity for the health plans, brokers and / or exchange operators.15

Conclusion

Private exchanges utilize a defined contribution for healthcare premiums to control costs and “offload” the inevitable growing cost burden to employees. Higher (indirect) absenteeism and presenteeism is likely due to the growing unaffordability of healthcare – especially to lower and moderate income households. Longer term, the deferral of medical treatment in at-risk employees and their families, and a reduction in the ability of employers to directly influence care delivery in their areas of geographic concentration, will result in higher healthcare costs for all concerned.

Footnotes

1Private Health Care Exchanges Enroll More Than Predicted. NY Times, June, 2014.

2 Kaiser / HRET Survey of Employer Sponsored Health Benefits, 2014.

3 PwC 2014 Touchstone Survey results published in The Rise of Retail Health Coverage; Sept. 2014.

4 Employee Benefit Research Institute. Self-Insured Health Plans: State Variation and Recent Trends by Firm Size,” and “All or Nothing? An Expanded Perspective on Retirement Readiness, November 2012.

5 Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust: Employee Health Benefits Survey, Sept. 2014.

6 Press Release. Aon Hewitt Analysis Shows Lowest U.S.Healthcare Cost Increases in More Than a Decade; Oct. 17, 2013.

7 Advisor Perspectives – Short D.Real Median Household Income: Month-over-Month Slippage But Off Its 2011 Low; Dec.31, 2013.

8 CDC Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011.Vital and Health Statistics, Series 10 (256); Dec. 2012.Table 17

9 Kaiser Family Foundation. “How Competitive are State Insurance Markets?” Oct. 2011.

10 McClellan M, McGinnis JM, Nabel J, Olsen L. Institute of Medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine and the Changing Nature of Healthcare: Meeting Summary (IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine); 2008.Table S-1, page 10.

11 The Commonwealth Fund. Hospital Cost of Care, Quality of Care, and Readmission Rates: Penny Wise and Pound Foolish? Archives of Internal Medicine, Feb.22, 2010; 170(4):340–46

12 Hussey P, Wertheimer S, Mehrotra A.The Association Between Healthcare Quality and Cost: A Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine 2013; 158 (1):27-34

13Private Health Insurance Exchanges Unleash 'Transformational Change'; Forbes.com, Jan. 2014.

14Towers Watson Buys Private Benefit Exchange Operator; The Motley Fool, Nov. 2013.

15Private Health Insurance Exchanges Unleash 'Transformational Change'; Forbes.com, Jan. 2014.