The Impact of Tightening Travel Restrictions on the Outlook for U.K. Airports

Declining passenger numbers continue to create balance sheet pressures

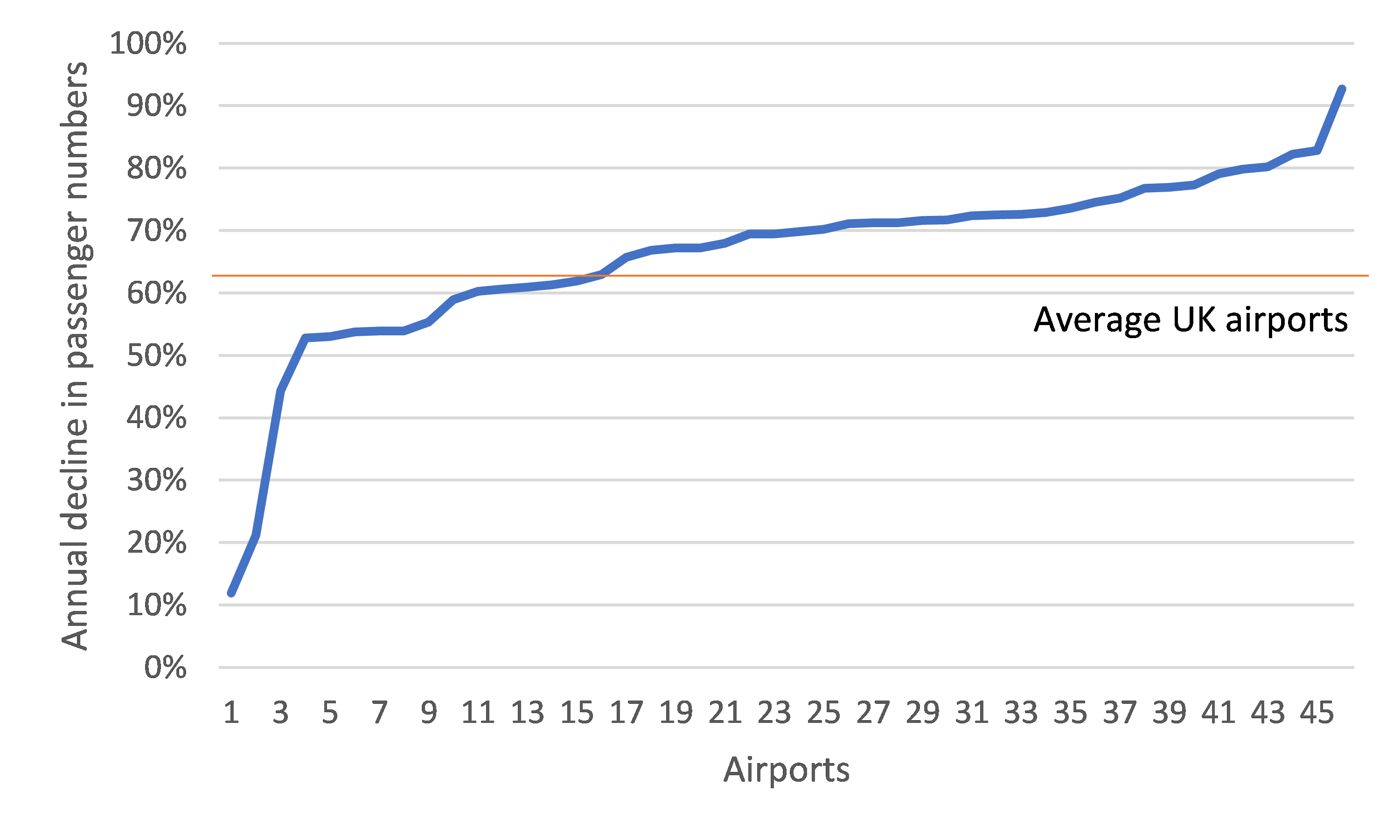

Ten months after the first lockdown, airport business models are under pressure as passenger volumes continue to decline. In November 2020, average annual declines in passenger numbers were 69% (see Figure 1), although traffic volumes had fallen by over 90% for some smaller regional airports traffic.

Figure 1: Annual decline in passenger numbers

Source: A&M analysis based on CAA data for 47 U.K. airports, November 2020 compared to November 2019

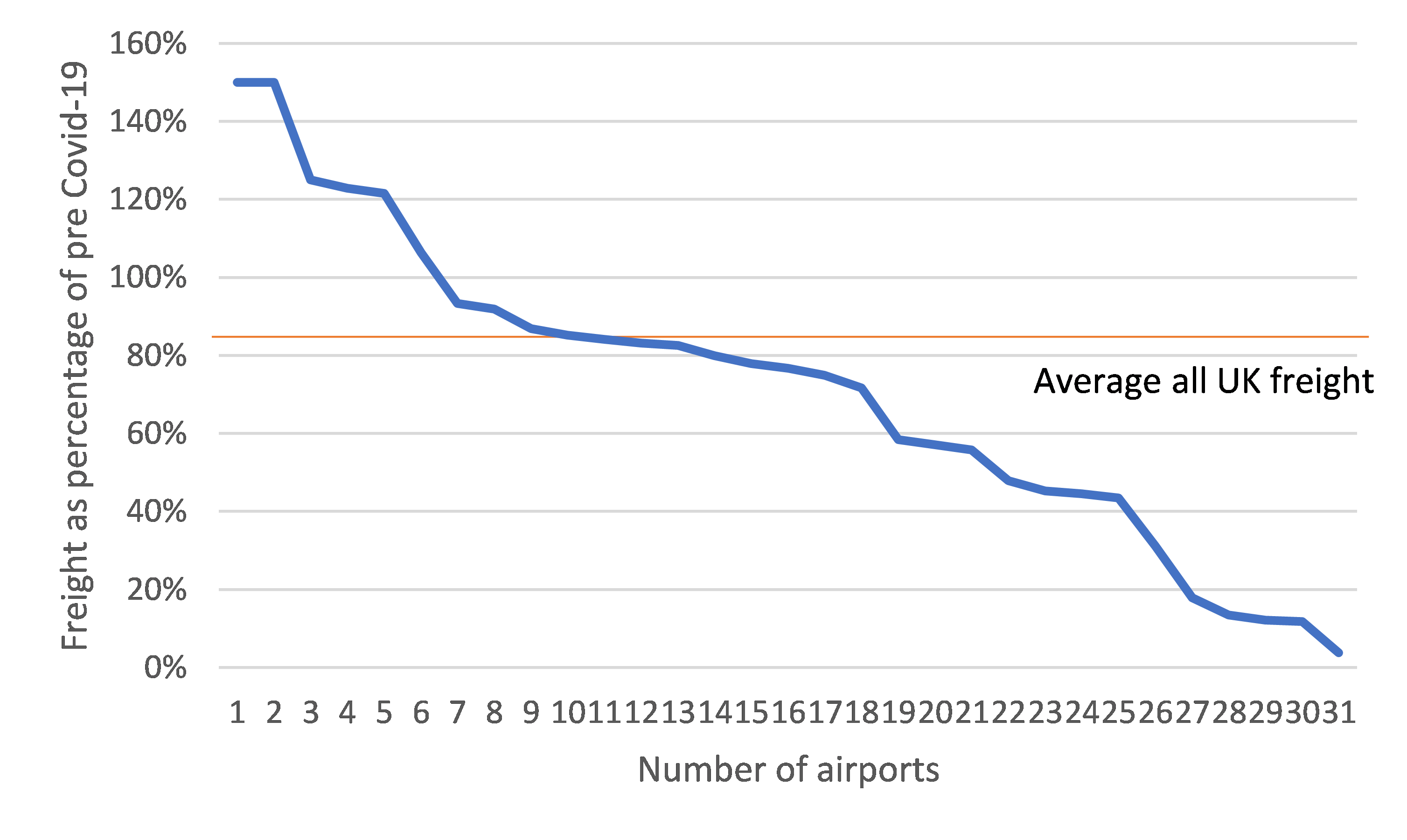

Freight volumes have held up better than passenger numbers, with a 17% reduction in November 2020 compared to November 2019 (see Figure 2). However, this hides vast differences between airports, as freight has been consolidated to hubs, with increased volumes at some of the smaller airports which are more difficult to reach by road or train.

Figure 2: Annual change in freight

Source: A&M analysis based on CAA data, November 2020 compared to November 2019 based on 31 U.K. airports

As of December 2020, European airline share prices were 25% down on the prior year , however, this included a 9% bounce in November 2020 as expectations around a vaccine rallied, and the potential for travel from Easter 2021 onwards were factored in. IATA reported, based on a sample of 15 European airlines show, that EBIT margins declined to an average of -45% in December 2020 from a +17% a year earlier with free cash flow reducing from 0% to -75% over the same period.

Airports are taking action to conserve cash within the business and access additional funding from external sources or Government support programs. However, whilst many have quite rightly focused on short term liquidity, the knock-on effect has seen an increase in liabilities on the balance sheet, such as HMRC liabilities, existing debt interest roll-up and additional debt, which will need to be repaid or restructured at some point in the future.

Expectations of passenger numbers rebounding during summer 2021 have been dashed by new public health rules, leading to increased pessimism from investors

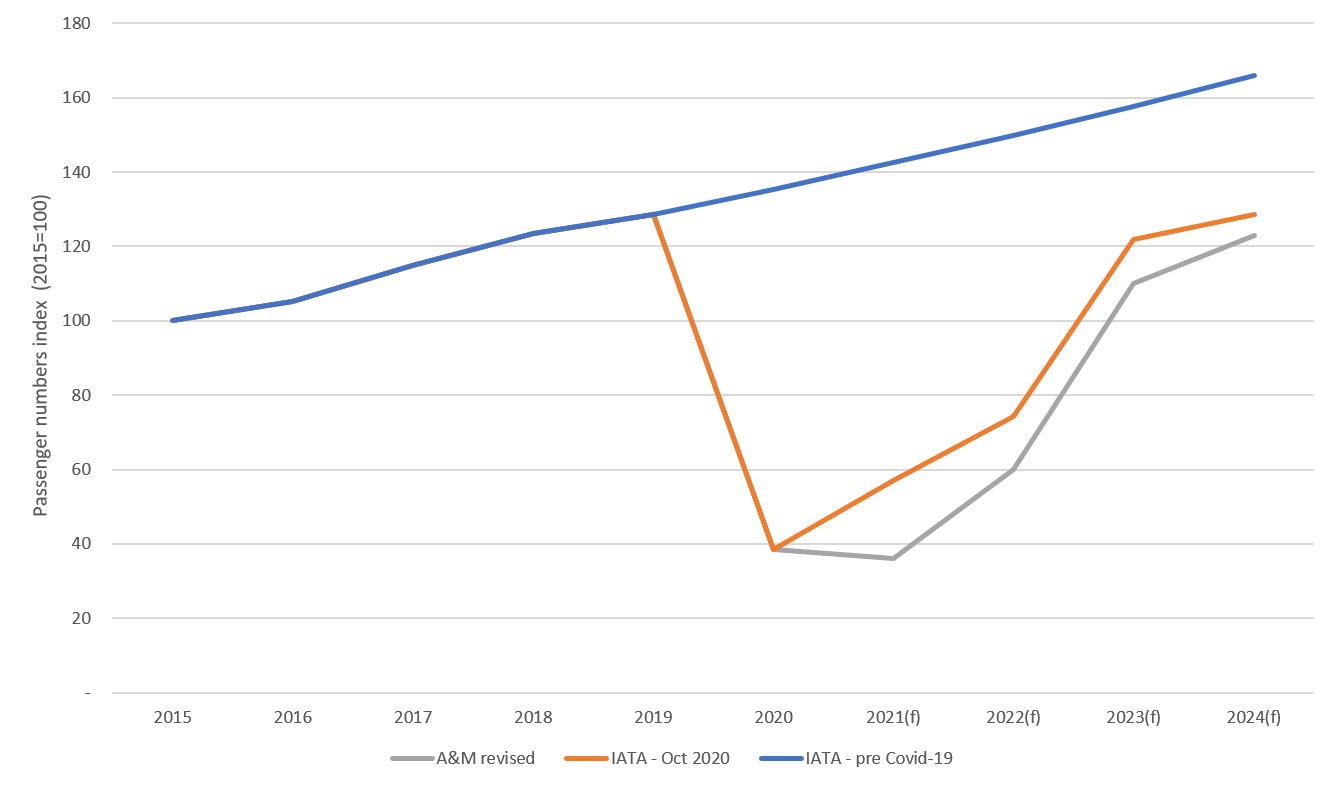

With the introduction of new quarantine and public health requirements alongside prolonged falls in GDP, passenger numbers and corresponding financials are not expected to rebound anytime soon. Indeed, passenger forecasts published towards the end of 2021 now look optimistic and it is expected that it will be 2023 at the earliest before passengers reach pre-Covid 19 levels (see Figure 3).

Whilst passenger numbers will eventually rebound, there is an indication that they may not quickly recover to pre-Covid levels. Airports have historically been classic, GDP linked assets with passenger volumes fluctuating in line with a multiple of GDP. However, changing behaviour driven by the pandemic may have a longer-term impact including a permanent reduction in business travel. Ultimately, as for leisure travel sector as a whole, this would be expected to rebound strongly, but is highly dependent on both public health measures and public confidence in both the safety of travel and the absence of “cancellation” risk.

Figure 3: Forecast number of European passengers (arriving or departing from EU airports)

Source: IATA actuals to October 2020.

IATA forecasts as at October 2020 based on IATA forecast European growth rates to 2022 and global growth rates after this point.

A&M revised based on A&M forecasts at January 2021, considering revised data on economic output, vaccine roll out and public health interventions including quarantine hotel measures.

A&M’s discussions with airport management and investors during autumn 2020 indicated an expectation of passenger volumes beginning to recover from Easter 2021, with summer 2021 short-haul volumes being key to financial sustainability. Most had sufficient financing in place through to Easter 2021.

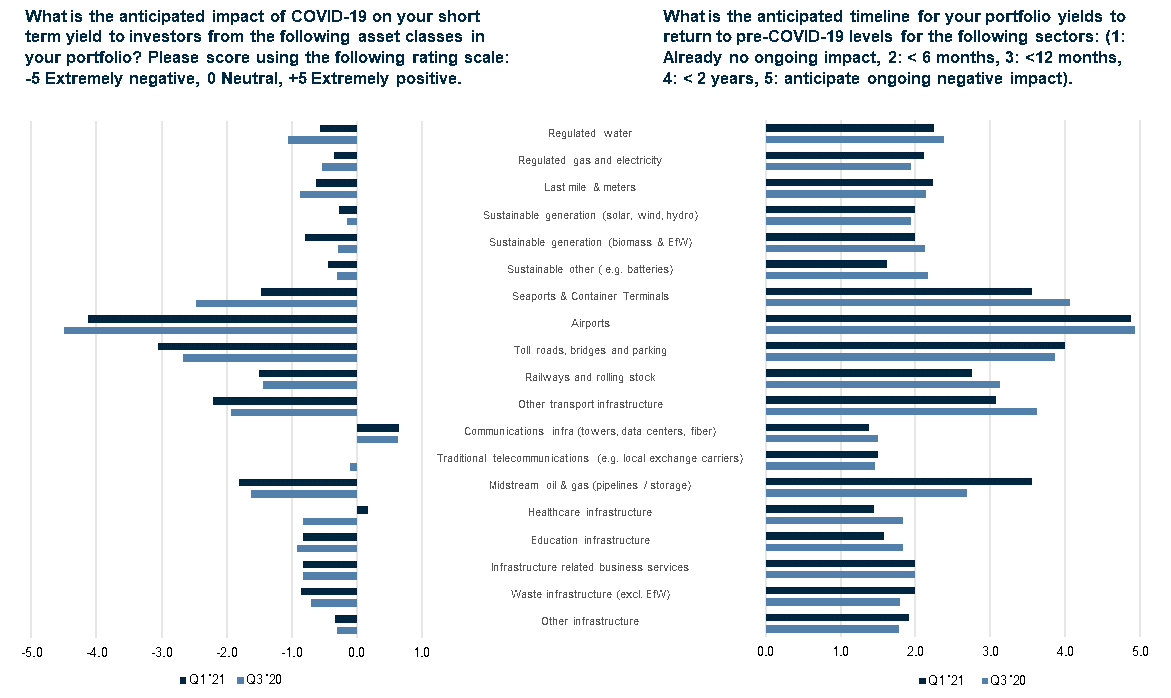

Over the last month, as governments have increasingly discussed and then implemented greater travel restrictions, the mood has become more pessimistic. Based on A&M’s most recent Quarterly Infrastructure Pulse (Q1 2021), a survey designed to provide a regular temperature check of sentiment in the sector, fund managers considered airports to have the most negative outlook, and was the only sector considered to be “permanently” impacted and unlikely to return to pre-COVID-19 yield levels (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Expectations of recovery profile from Covid-19

Source: A&M analysis based on survey conducted of GIAA members, January 2021.

Airport owners and investors need to mitigate against a prolonged drop in passenger numbers

Without substantial 2021 summer traffic, most airports’ cash drain will likely continue with the associated pressure on the ability to service debt and headroom against facilities, already extended by lenders. Without decisive actions by the key sector stakeholders, bankruptcy of the weakest airlines will accelerate and put further pressure on airports.

To date, lenders, alongside equity from shareholders, have been supportive and “kicked the can down the road” in the expectation of a summer 2021 recovery. With that looking increasingly unlikely, there is an increasing risk particularly for the weaker regional airports which relied on “convenience” for travellers rather than a strategic necessity.

Most airports and their owners will now be reviewing their business plans in the light of these new lower predicted passenger volumes and considering their options. Shorter-term actionable steps to ride out the storm and stem the flow of cash from the business include:

Reducing costs by suspending services and repurposing assets: Temporarily suspending passenger flights, focussing on freight, is one option. The impact on cash position will depend on regulatory and contractual obligations, fixed versus variable costs and requires consideration against restructuring passenger flights and contracts with airlines and retailers to make a positive contribution towards fixed costs. Where freight volumes alone are not economically viable, mothballing a terminal or an airport may be another option.

Space freed up from service reductions could be put to alternative uses, for example, vaccination centres, office space or warehousing, noting that warehousing space outpaces supply in the U.K. driven by booming eCommerce sales. Pre-certified airport employees could be redeployed to provide logistical support to these warehousing companies.

Employee costs (c30% of operating costs) are being optimised through government schemes. However, all remaining costs need to be moved to a variable basis wherever possible.

Financial restructuring and liquidity options: As cash is drained, we expect airports to be engaging with lenders and government and restructuring debt. Restructuring plans may include use of court driven process e.g scheme of arrangement. Government support could come in the form of loans, equity stakes, investing in related infrastructure or changes to the tax and duty regime.For example, seeking revisions to the Government’s Airport and Ground Operations Support Scheme which allows for only £8m per applicant business rate relief and therefore disadvantages larger airports who may pay as much as £120m per year in rates and adjustments to the airport duty free regime.Such a request from the airport will need to be framed to comply with the post-Brexit U.K. subsidy regime and appeal to wider government objectives, including environmental and sustainability motivations.

Alongside restructuring debt, renegotiating third party arrangements with service providers to reflect reduced demand forecasts will improve liquidity. This may take place through a voluntary arrangement, alternatively, some commercial contracts contain re-openers upon exceptional events.

Preparations for when traffic rebounds: Whilst airports remain largely empty of passengers, this presents an opportunity for airports to:

- consider their strategies in the light of emerging drivers, including environmental and sustainability; and

- to undergo transformation programmes to ensure that they are in the best position to maximise on passenger numbers and revenues when air travel does recommence. One example would be accelerating the deployment of digital solutions to improve the passenger experience and optimising back of house services such as baggage handling.

Airports could consider tendering available space in terminal and repurposing retail space, asking for upfront payments, from interested new concessionaires who want to take advantage of the rebound when traffic comes back.

Human capital is key to successfully operating an airport and, in part due to the availability of furlough schemes, may not have been at the fore of airport restructuring plans to date. Whereas the initial response focussed on managing the crisis, there is now an understanding that airports are in this for the long haul and solutions around staffing need to developed and communicated. The importance of facilitating resilience and motivation, alongside capability and capacity, should not be underestimated as enablers to recovery.

COVID-19 may prompt more fundamental structural changes, with airports merging or regional closures

Although we expect passenger volumes to largely rebound by 2024, Covid-19 has highlighted structural inefficiencies. Competition amongst airports and airlines when neither can make money without capturing more than 100% of the market is destructive and in normal circumstances would lead to a reduction in capacity. In some cases, it may make economic sense to form consortiums across competing travel infrastructure to concentrate demand on only one infrastructure, e.g. closing one airport with the transfer of capacity to boost traffic in the nearby competitor(s) for the benefit of all. In this case the closing airport would be expected to receive an indemnity payment to justify closure (indexed on incremental traffic volume). Alternatively, airports may focus on “hub and spoke” model deals with airlines, looking to build capacity around specific airlines noting that international connections to secondary airports may be impacted for many years as airlines consolidate traffic at hub airports.

In the longer term, we may see the closure of some regional airports, particularly where they rely on domestic travel that can be replicated by train or car or have another larger airport nearby which is better positioned to service this changing market. This may spark competition concerns with regulators, however whilst over-capacity remains these concerns may be limited and in the longer term this could be managed with price controls or other regulation if needed.

Whatever the specific situation, we believe that U.K. airports need to review all the options and select a short list for further evaluation to support a revised business plan. It is critical to consider the near-permanent impact on the sector in support of refinancing or financial restructuring discussions now.

How A&M can help?

A&M has decades of experience working with leading airport operators and owners in Europe, the Americas, Middle East and Asia - advising them on performance improvement, operational and financial restructuring, transaction due diligence, regulatory strategy and valuation. We have a number of professionals who have senior management experience in the sector, and have worked directly with the government on critical regulatory issues facing the sector. At A&M, we provide a unique combination of leadership, operational experience and financial/econometric skills to help airports take action to deal with the current crisis.