The Devil is in the Details: Practical Tips to Evaluate Management Forecasts

We’ve all seen financial models that utilize management projections to quantify value of some sort – perhaps it’s in a discounted cash flow analysis or a lost profits damage assessment. They can be highly technical, look fancy, and purport to set forth the resulting value with some sort of economic precision. But the results are only as good as the inputs, the most critical of which is often a financial forecast or projection prepared by management.[1]

It’s true – the subject company’s management should have the best insight into the expected future performance of the business. However, management can also be, perhaps unknowingly, subject to forecast bias. I recall sitting in on a CFO’s deposition in which he was asked about the achievability of the multi-year forecasts prepared by the head of the company’s planning and analysis group. His response: “[Mr. X] never prepared a forecast he didn’t love.” Aside from disregarding management forecasts due to this bias or blindly accepting them under the premise of “management knows best,” are there methods to objectively evaluate management forecasts for reasonableness?

In this article, I discuss practical considerations that may assist in the evaluation of management forecasts.

Key Considerations When Evaluating Forecasts:

1. Why was the forecast prepared?

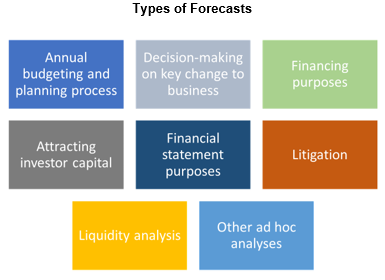

Understanding why a forecast was prepared can be important. Most companies develop forecasts as part of a regular budgeting and planning process. However, management may also create forecasts for a variety of other purposes, such as to obtain financing, attract investors, test financial statements for impairment, or evaluate a planned investment, acquisition or divestiture. Each of these purposes may impact the forecast itself, the rigor with which it was prepared, the degree of embedded conservatism or stretch, and whether the forecast is dependent on the uncertain execution of a hypothetical assumption.

Typically, all else being equal, a financial forecast that was prepared in the ordinary course of business as part of a recurring periodic process may be more reliable than one prepared for the purpose of a singular transaction or for litigation purposes. However, this is not to say these latter types of forecasts are invalid, nor that an ordinary course forecast is necessarily reasonable. Absent any other data or analysis, though, considering the purpose of the forecast may impact the weight to which management’s forecast is provided.

2. How was the forecast prepared?

Let’s assume we are evaluating a financial forecast prepared by management in the ordinary course of business as part of a recurring annual budgeting and planning process. Even with this simplifying assumption, all financial forecasts are not created equally. Additional consideration of how the forecast was prepared may be helpful.

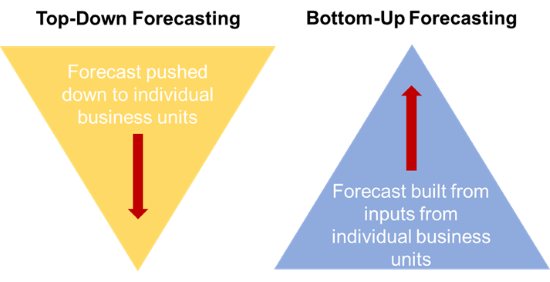

As an example, assume two hypothetical national appliance retailers both prepare three-year financial forecasts annually. Under significant pressure from the majority owner to exhibit growth, Tom’s Appliance Store prepares its annual forecast by taking the prior year’s results for each store and adding 10 percent revenue growth for each of the three forecasted years. The resulting goal for each store is communicated by top level management to each of the store managers, and store management is expected to find a way to meet the target. This is different from the approach utilized by Wendy’s Appliance Warehouse for which individual store managers develop their annual forecast based upon local market factors, including detailed assumptions regarding pricing, expenses and consumer demand expected during the forecast period.

Key takeaway

In this example, Tom’s Appliance Store relies upon a top-down approach to forecasting, whereas Wendy’s Appliance Warehouse utilizes a bottom-up approach.

All else being equal, Wendy’s financial forecast may be more reliable than Tom’s, although in reality the ability to execute on a forecast may be more important than the methodology utilized to create it (see additional discussion at #5 below).

3. Is the forecast in line with the company’s past performance?

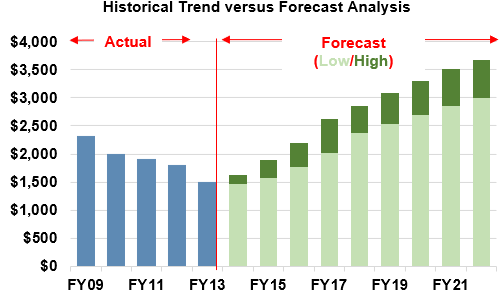

We’ve all heard the term “hockey stick projections” and have likely seen it in practice. The chart below shows the historical versus forecasted revenue for a particular product line subject to an asset valuation in an actual case in which I was involved a few years back. Clearly, the actual historical revenue from fiscal year 2009 through 2013 demonstrated a consistent decline. To the contrary, the forecast, which included both a “low” and a “high” scenario, projected an almost immediate turnaround in the revenue, with even the low scenario rebounding with consistent year-over-year growth.

Forecasts that are consistent with historical performance and trends – revenue, EBITDA, growth rates, margins – may be more reasonable than those that demonstrate hockey stick performance. When dealing with a dichotomy between management’s forecasts and historical performance, it may be useful to seek to understand the rationale for the change. Has there been a change in the industry, such as a cleared regulatory hurdle, a geographic expansion, a recent acquisition or new product line, a key pricing change, or other marketing or promotional activities? If examining earnings or margins, were cost cutting measures put in place by the company?

Key takeaway

There very well may be valid reasons for management’s forecast diverging from historical results, but without an understanding of these underlying factors, a financial forecast that mirrors historical performance may be viewed as more reasonable than one that does not.

4. Is the forecast in line with industry expectations?

In addition to anchoring the forecast in a company’s own historical performance, it may also be useful to anchor the forecast to expectations for the industry overall. Industry reports, such as those prepared by IBISWorld, typically provide expected growth rates for whole industries and a discussion regarding the factors impacting the industry’s growth estimates. Examining publicly available information from peer or competitor companies may provide similar insight.

Particular circumstances, however, may warrant careful definition of “the industry” – for instance, expectations for a particular geography may even provide greater utility than the industry overall. Consider a construction supply company for which management is forecasting 10 percent revenue growth. While industry reports for the overall construction industry may estimate only three to five percent expected growth rates, it may be that the subject company is located in a particularly hot real estate market, and local data supports management’s 10 percent growth forecast.

Key takeaway

While certainly not the only relevant factor, industry and peer company estimates may provide instructive comparison points when evaluating a forecast prepared by management. When possible, the ability to reconcile any similarities to or differences from industry expectations may strengthen the reliability of management forecasts.

5. What is the company’s track record with regard to its forecasts?

Assuming management utilizes a consistent process year-over-year when creating its financial forecasts, it can be very insightful to compare the company’s prior year forecasts with the actual achieved results for those forecasted years in order to answer a very critical question – how good is management at forecasting?

Importantly, this type of analysis does not merely entail looking at the financial forecast in question and comparing it, in isolation, to whatever the known results are in between its creation and now. Such an analysis may be flawed for considering hindsight (in a business valuation) or for not considering the impact of the alleged actions (in a damage assessment). Instead, a more appropriate analysis looks back historically at previous forecasts prepared by management and analyzes how close the company came to achieving those forecasts.

For instance, it may be helpful to review the previous five years of annual forecasts prepared by management compared to actual results. If management’s forecasts typically fell within a reasonable range, plus or minus, from the actual results, it may provide additional credibility to the subject’s financial forecast. On the other hand, if management historically missed its forecasted metrics by wide margins year after year, it may be an indication that management’s forecasting process does not produce very reliable results, or at least that more questions may need to be asked. A third alternative is that the company may be good at forecasting near term results but significantly less accurate when it comes to forecasting outer years.

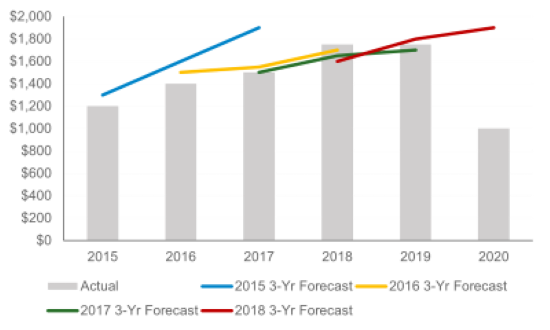

Let’s review an example for a hypothetical company, Matt’s Market. The chart below summarizes historical sales relative to Matt’s annually prepared three-year forecasts.

In this example, it’s clear that if single forecasts were viewed in isolation, one may conclude based on the 2015 or 2018 forecasts that Matt’s Market was not very good at preparing projections. A deeper analysis, however, may uncover that Matt’s Market switched from a top-down to a bottom-up forecasting process in 2016, after which its forecasts became much more accurate, and that the large miss in 2020 was almost exclusively due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic rather than a flawed forecasting process.

Key takeaway

While comparing historical sales relative to annually prepared forecasts may raise additional questions, it can be a good starting point to assess management’s track record with respect to its forecasts.

6. What if the forecast is for a new business?

A financial forecast for a new business that has yet to commence operations provides a unique set of challenges. The forecast cannot be anchored to the subject company’s past performance, either in historical results or in historical forecasting ability. In such instances, it may be more important than ever to compare the forecast, or its individual component assumptions, to third-party benchmarks and market data.

Conclusion

While not intended to be an exhaustive list, the considerations discussed herein provide examples of the types of questions and analyses that may help in assessing the reliability of management’s projections. It is important to note, however, that there is no one size fits all approach to analyzing a financial forecast, and it often depends on the availability of certain data and access to management personnel to provide specific insight.

[1] Different companies utilize different terms – forecast, projection, budget, plan, to name a few. While there can be a technical difference between the various terms, for ease in this article, I utilize the term “forecast.”