The BEAT: A Tax Aimed at Large Corporations Actually Hits Many Small Ones

Article featured on Thompson Reuters' Taxnet Pro, August 2019.

As we enter the height of the 2018 compliance season, many taxpayers are wrestling with the nuances of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act for the first time. They are, in many cases, brought about by virtue of the new and modified IRS forms, which demand a substantial amount of disclosure relative to prior years. One surprise catching taxpayers off guard is the scope of the base erosion and anti-abuse tax, or BEAT.

Despite being advertised as a tax on ‘large’ corporations, the BEAT’s aggregation rules can rope in taxpayers who had believed themselves to be far beyond its grasp. Even if not subject to BEAT taxation, many companies will be surprised at the level of reporting that is still necessary. This article discusses potential BEAT traps that all corporate taxpayers should review immediately.

BEAT Refresher

The BEAT operates as a minimum tax on corporations that make substantial deductible outbound payments to foreign related parties (referred to as “base erosion payments”). Taxpayers are required to compute a modified taxable income by adding back the tax deductions associated with such payments and subjecting the modified taxable income to a 10 percent tax rate (five percent for 2018; 12.5 percent after 2025). If this tax exceeds regular tax, the taxpayer owes the difference.

Congress advertised the BEAT as a tax on corporations with substantial gross receipts, limiting its applicability to companies with U.S. annual taxable gross receipts of at least $500 million (based on a three-year average). Additionally, the BEAT does not apply to taxpayers whose deductions for base erosion payments are less than three percent of total deductions (the “base erosion percentage”). If both thresholds are exceeded, the corporation is considered an “applicable taxpayer,” and subject to the BEAT.

The trap…

Many taxpayers, particularly those that are privately owned (or related to a privately-owned company), will be surprised by the scope of the applicable taxpayer rules. Such rules require taxpayers to aggregate their gross receipts and base erosion percentage with those of certain related parties.

Aggregation of Related Parties

While the comparison of the BEAT minimum tax to regular tax is performed at the level of a single taxpayer, the determination of whether a corporation is an applicable taxpayer is performed at a controlled group level. A corporate taxpayer must measure its gross receipts and base erosion percentage on an aggregate basis with other members of its controlled group.

For these purposes, a controlled group can include a:

- Parent-Subsidiary Controlled Group: one or more chains of corporations that share a common parent corporation, where each corporation (except the parent) is owned more than 50 percent (measured by vote or value) by one of the other corporations.

- Brother-Sister Controlled Group: two or more corporations, if five or fewer individuals, estates or trusts own more than 50 percent (measured by vote or value) of each corporation (taking into each of the five or fewer persons’ stock ownership only to the extent it is identical with respect to each corporation).

- Combined Group: three or more corporations, one of which is a parent in a parent-subsidiary controlled group and is a member of a brother-sister controlled group.

These baskets apply constructive ownership rules in determining whether two corporations are members of a common controlled group. For example, stock owned by a partnership is considered proportionally owned by any partner with a five-percent-or-more interest in the capital or profits of the partnership.

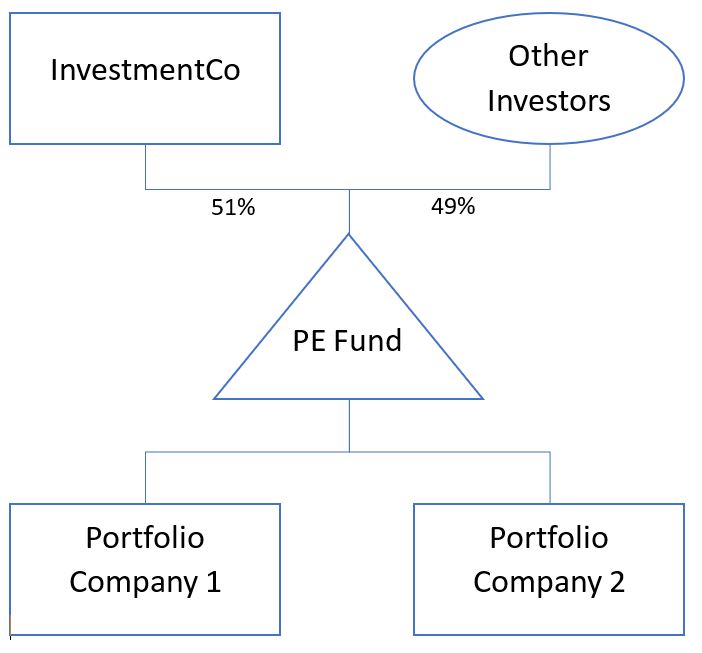

Furthermore, the ‘combined group’ bucket allows these rules to be applied iteratively so that a controlled group can extend well beyond simple structures, such as a U.S. consolidated group or two U.S. corporations under a common foreign parent. Consider the following example:

In this fact pattern, InvestmentCo is considered a common parent to both Portfolio Companies after considering its constructive ownership through a PE Fund. Accordingly, all three U.S. corporations are considered part of a common controlled group, and their gross receipts and base erosion percentage must be calculated on an aggregate basis.

To further complicate matters, perhaps InvestmentCo has similar investments in other funds! The net can become wider and wider as more facts are uncovered.

Consider also circumstances in which a US corporation has issued multiple classes of stock with different voting rights. Taxpayers will need to consider whether any given shareholder’s interest in the vote or value exceeds half of the total vote or value of the corporation. This may occur, for example, in the context of non-voting preferred stock that exceeds the value of the issuing corporation’s common equity.

Challenges for 2018 Compliance

As supported by the above examples, the greatest obstacle for many taxpayers in applying these rules is a lack of information. Few privately-held corporate taxpayers have sufficient visibility into their ownership structure beyond their direct shareholders, and fewer still will have access to the gross receipts and base erosion percentage detail of members of their controlled group.

Nevertheless, new Form 8991 requires taxpayers who meet the gross receipts test (on the aggregate basis) to report the gross receipts and base erosion payments of their controlled group. This may be impractical or impossible for many companies, and especially frustrating when that taxpayer has no incremental BEAT tax. However, failure to report the required information (even if the taxpayer can otherwise prove they owe no BEAT tax) may leave the statute of limitations open for the tax return. As such, the IRS may make the default assumption that a corporation is an applicable taxpayer unless it can prove otherwise.

Consider perhaps an even more costly fact pattern: a corporation thinks it is an applicable taxpayer, but if it were to aggregate with its controlled group properly, its base erosion percentage would fall below three percent. In this case, a lack of knowledge causes the taxpayer to pay BEAT tax when it was never subject to the BEAT in the first place!

Given the challenge many taxpayers will face in identifying their controlled group members, the priority this compliance season should be on communicating with shareholders and mapping out the boundaries of the controlled group. At a minimum, and until the IRS considers a more practical approach, gathering as much information as possible and showing a good faith effort to report may be sufficient for taxpayers to be considered in substantial compliance.

A&M Taxand Says:

With only a few short weeks until calendar year 2018 returns are due, taxpayers should be making every effort to piece together the puzzle of their controlled groups. Identifying members and proactively sharing information may be an inconvenience, but it is ultimately preferable (for each member and its common stakeholders) to the risk of the IRS presuming ‘applicable taxpayer’ status, and of an incomplete return.