Ending the Duplicity - Section 362(e)(2) and Loss Duplication Transactions

2013 - Issue 46—Everyone loves a good deal, and the only thing better than a good deal is a great deal. Since the enactment of the federal income tax in 1913, certain taxpayers have looked for ways to structure their affairs to get a great deal for tax purposes. One example of what used to be a great deal for tax purposes is what is referred to as a “loss duplication transaction,” which is broadly defined as a transaction that generates multiple tax losses for one corresponding economic loss. If that sounds like a great deal, that’s because it is, so much so that the Internal Revenue Service has spent decades combating it on the principle that it’s just too good to be true.

Many high-profile taxpayers have participated in loss duplication transactions. As one example, in the wake of the collapse of Enron, Congress found that Enron had been participating in various incarnations of loss duplication transactions prior to its demise. In response, in 2004, Congress enacted Section 362(e)(2) as part of the American Jobs Creation Act in order to curtail a certain vintage of loss duplication transactions that were being undertaken by various taxpayers.

Although most of these transactions have been quashed, either through legislative action or judicial fiat, taxpayers are still dealing with the effects of the fallout — as with one example that was almost 10 years in the making, when on September 3, 2013, the Treasury Department and the IRS issued final regulations that provide important and specific guidance to taxpayers that undertake transactions governed by Section 362(e)(2), principally tax-free transfers of property to corporations, such as in the context of incorporating a business that was previously organized as a partnership or sole proprietorship.

This edition of the Tax Advisor Weekly provides an overview of the federal income tax rules governing the formation of, and transfer of property to, corporations and the implications under Section 362(e)(2).

Background: the Interplay Between Sections 351 and 362(e)(2)

In the absence of any other applicable provisions, the transfer of property to a corporation in exchange for stock would generally be a taxable transaction under federal income tax law. Recognizing that the transfer of property to a corporation in exchange for stock was not necessarily the appropriate time to levy the federal income tax, Congress provided that transfers of property to corporations, in exchange for stock that met certain requirements, would not be currently taxable. This provision currently manifests itself in Section 351, which provides that a shareholder will not recognize gain or loss if the following requirements are satisfied: (i) the shareholder transfers property to the corporation (with property including almost any type of asset that may be transferred, but specifically excluding services); (ii) in exchange for such property, the shareholder solely receives stock of the corporation (which can be either common or certain types of preferred stock and can be either voting or nonvoting); and (iii) immediately after the exchange, the shareholder is in control of the corporation, which generally means the shareholder owns stock constituting at least 80 percent of the stock entitled to vote and at least 80 percent of the total number of shares of all other classes of stock of the corporation.

Assuming these requirements are met, the shareholder would not recognize gain or loss, and in general would receive a substituted tax basis in the stock acquired equal to the tax basis in the property transferred (with certain other adjustments). The corporation, too, will not recognize gain or loss, and will receive a carryover tax basis in the transferred property equal to the shareholder’s tax basis in such property immediately prior to the transfer. In the case where property with a built-in gain is transferred, Section 351 operates to shield the shareholder from recognizing gain on a current basis, and post-transfer, the built-in gain is reflected in the shareholder’s stock, which will ultimately be recognized if the shareholder subsequently disposes of such stock in a taxable transaction.

As a result of the rules discussed above, prior to the enactment of Section 362(e)(2), taxpayers were able to exploit a quirk in the law, undertaking tax-motivated transactions by transferring built-in loss property to a corporation and then disposing of the property, resulting in the recognition of two tax losses for only one corresponding economic loss. For example, Shareholder X transfers property with a tax basis of $100 and a fair market value of $50 (i.e., a $50 built-in loss property) to Corporation Y for 50 shares of Corporation Y stock. Assuming all other requirements of Section 351 are satisfied, and in the absence of Section 362(e)(2), Shareholder X would receive a substituted tax basis in the stock acquired of $100 (equal to Shareholder X’s tax basis in the transferred property) and Corporation Y would receive a carryover tax basis in the property of $100 (equal to Shareholder X’s tax basis in the property immediately prior to the transfer). What was once one built-in loss has now become two (i.e., in Shareholder X’s stock and Corporation Y’s property). This inequitable result allows Shareholder X to sell his shares at the fair market value of $50 and recognize a $50 loss, as well as allowing Corporation Y to sell the property at the fair market value of $50 and recognize a $50 loss. Absent a fix for this glaring loophole, taxpayers could effectively “import” built-in losses into corporations and then duplicate such losses as described above. For obvious reasons, this result could not stand.

Section 362(e)(2) — Congress’s Complicated Solution to a Relatively Simple Problem

Congress is known for many things, but pursuing the path of least resistance with respect to tax matters is not one of them. Congress sometimes has a knack for creating exceedingly complicated solutions to relatively simple tax issues. For example, Section 362(e)(2) operates in a peculiar way to curtail the types of loss duplication transactions that are detailed above. It provides that if property is transferred in a tax-free transaction, namely a Section 351 transaction, in which the transferee’s (i.e., the corporation’s) tax basis would exceed the fair market value of such property, then the transferee’s tax basis is reduced so as not to exceed fair market value. For purposes of this article, this is referred to as the “Step-Down Rule.” The Step-Down Rule is a common-sense solution to the duplicated loss problem in instances where only one asset is transferred. The statute operates to eliminate the transferee’s built-in loss, and as a result, there is no further possibility that the taxpayer and the corporation can collude to undertake further transactions that result in a duplicated loss.

The complication arises when multiple assets are conveyed to a corporation as part of a single overall transfer, such as in the case of an incorporation of a business. The statute specifically states that one must compare the aggregate tax basis of the transferred assets to the aggregate fair market value of such assets in determining whether the Step-Down Rule is operative. Thus, if multiple assets are transferred to a corporation in a transaction meeting the requirements of Section 351 and certain assets have a built-in loss, but when viewed in the aggregate the combined tax basis is less than or equal to the combined fair market value, then the Step-Down Rule remains dormant. But if in the aggregate the combined tax basis of the transferred assets exceeds the combined fair market value, then the Step-Down Rule is implicated and must be applied.

In what is somewhat reminiscent of a Rube Goldberg machine, Section 362(e)(2)(B) details the procedures to be undertaken when assets are transferred to a corporation in a tax-free transaction and the aggregate tax basis of such assets exceeds the aggregate fair market value, necessitating the application of the Step-Down Rule. If all of the assets transferred have a built-in loss, then the tax bases of all assets are stepped down to fair market value, similar to what happens when a single asset with a built-in loss is transferred as described above. However, when multiple properties are transferred, some with a built-in-loss and some with a built-in gain, the rules mandate the following: the proportionate share of built-in loss of each property (excluding any built-in gain in property) is multiplied by the overall transaction’s built-in loss (including any built-in gain in property) and then subtracted from the tax basis of each built-in loss property.

Confused Yet? Step-Down Rule Example

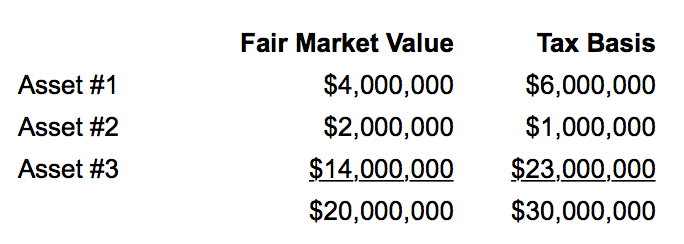

John Doe owns all of the stock in JD Corporation. John transferred the following three properties to JD Corporation in exchange for 1,000 shares of JD Corporation stock in a transaction qualifying for Section 351:

John Doe will take a $30 million carryover basis in the 1,000 shares of JD Corporation. Pursuant to Section 362(e)(2), JD Corporation’s tax basis in each of the three assets is calculated as follows:

Assets #1 and #3 have a built-in loss totaling $11 million (i.e., $2 million for Asset #1; $9 million for Asset #3). Each asset’s proportionate share of built-in loss is multiplied by the transaction’s aggregate built-in loss (i.e., $10 million, after the $1 million built-in gain of Asset #2 is netted with the $11 million of aggregate built-in loss) and then subtracted from the original tax basis of the built-in loss assets, leaving aggregate tax basis equal to the assets’ aggregate fair market value.

The end result is that the aggregate built-in loss has been eliminated when viewed on an aggregate basis, but nonetheless the application of the Step-Down Rule leads to a seemingly convoluted result. While on an aggregate basis the built-in loss has been eliminated, Asset #1 and Asset #3 still have a built-in loss, though diminished, when viewed on an individual basis.

Section 362(e)(2)(C) Election

Recognizing that there might be business exigencies where taxpayers may want to preserve a built-in loss in property transferred to a corporation, Congress included Section 362(e)(2)(C), which allows the transferor and transferee (i.e., the shareholder and the corporation, respectively) to jointly elect to have the tax basis reduction applied to the stock received by the shareholder rather than the property received by the corporation. If such an election is made, the corporation would receive the property and take the shareholder’s tax basis immediately prior to the transaction and the shareholder’s tax basis in the stock would be reduced so as not to exceed its fair market value. In the example illustrated above, John Doe’s basis in the stock would be $20 million and JD Corporation’s basis in the three assets would be $6 million, $1 million and $23 million, respectively. The recently published final regulations mentioned above provide detailed guidance to taxpayers on the mechanics of making the Section 362(e)(2)(C) election.

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand Says:

Section 351 is a deceptively easy mechanism through which to transfer property to a corporation tax-free. However, due to Section 362(e)(2) and the regulations issued pursuant to it, shareholders are no longer able to undertake transactions that result in duplicate tax losses when there is only a single economic loss. This trap for the unwary makes proper valuations of property in connection with the incorporation of businesses (including check-the-box elections) or transfers to corporations exceedingly important.

Disclaimer

As provided in Treasury Department Circular 230, this publication is not intended or written by Alvarez & Marsal Taxand, LLC, (or any Taxand member firm) to be used, and cannot be used, by a client or any other person or entity for the purpose of avoiding tax penalties that may be imposed on any taxpayer.

The information contained herein is of a general nature and based on authorities that are subject to change. Readers are reminded that they should not consider this publication to be a recommendation to undertake any tax position, nor consider the information contained herein to be complete. Before any item or treatment is reported or excluded from reporting on tax returns, financial statements or any other document, for any reason, readers should thoroughly evaluate their specific facts and circumstances, and obtain the advice and assistance of qualified tax advisors. The information reported in this publication may not continue to apply to a reader's situation as a result of changing laws and associated authoritative literature, and readers are reminded to consult with their tax or other professional advisors before determining if any information contained herein remains applicable to their facts and circumstances.

About Alvarez & Marsal Taxand

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand, an affiliate of Alvarez & Marsal (A&M), a leading global professional services firm, is an independent tax group made up of experienced tax professionals dedicated to providing customized tax advice to clients and investors across a broad range of industries. Its professionals extend A&M's commitment to offering clients a choice in advisors who are free from audit-based conflicts of interest, and bring an unyielding commitment to delivering responsive client service. A&M Taxand has offices in major metropolitan markets throughout the U.S., and serves the U.K. from its base in London.

Alvarez & Marsal Taxand is a founder of Taxand, the world's largest independent tax organization, which provides high quality, integrated tax advice worldwide. Taxand professionals, including almost 400 partners and more than 2,000 advisors in 50 countries, grasp both the fine points of tax and the broader strategic implications, helping you mitigate risk, manage your tax burden and drive the performance of your business.

To learn more, visit www.alvarezandmarsal.com or www.taxand.com